As the Thyroid Pharmacist, I’m often asked whether my protocols will work for Graves’ disease and hyperthyroidism, as well as Hashimoto’s. While my clinical practice focuses primarily on hypothyroidism and the autoimmune condition Hashimoto’s, many of the same interventions I recommend for Hashimoto’s will work for many other autoimmune conditions, including Graves’ disease.

Although the symptoms of these seemingly opposite conditions can be quite different (and recommended symptom management strategies may differ as well), they actually have a lot in common regarding the root causes they can share (including infections, leaky gut, and stress).

Both conditions are destructive to overall health, but the excess thyroid hormone production present in most cases of Graves’ disease can create a very dangerous and urgent situation to treat.

Those that know me personally, know that I am a very cautious person who puts safety above all. I prefer working with clients in a lifestyle-based fashion, to gently reverse chronic conditions… and I prefer not to work in emergency situations. This is why I chose to become a triple-checking pharmacist, instead of an emergency room doctor or paramedic, after all. 🙂

For this reason, most of my clients with Graves’ disease have been post-radioactive iodine, post-thyroidectomy, or well controlled with thyroid hormone blockers prescribed by another clinician.

Thus, my experience with my clients with Graves’ disease has primarily focused on the autoimmune component of the condition (which is very similar to the approach with Hashimoto’s), and not on ways to manage their thyroid hormone levels.

As a pharmacist, I was initially a bit skeptical of natural thyroid blockers. I wasn’t sure they would be as effective as pharmaceutical medications. However, as I continue to learn more from my clients, colleagues, readers, research, and functional medicine training, I am now excited to share some information about helpful natural thyroid blockers, thanks to insights from two of my colleagues who have specialized in the functional medicine treatment of Graves’ disease: Dr. Sarah Zielsdorf and Dr. Eric Osansky.

Both of these knowledgeable doctors participated in my Thyroid Secret docuseries and have some wonderful information to share.

Dr. Osansky, was himself diagnosed with Graves’ years ago, and has learned a lot through his own health journey. He is a Certified Clinical Nutritionist, a Certified Nutrition Specialist, and a Certified Functional Medicine Practitioner from the Institute for Functional Medicine. He is a Doctor of Chiropractic who focuses on endocrine conditions.

Dr. Zielsdorf also has a wealth of info, and I am particularly excited for her to share her thoughts on the use of Low Dose Naltrexone in treating Graves’. She is board certified in Internal Medicine, and is an Institute For Functional Medicine certified physician. She is the owner and attending physician at Motivated Medicine.

I’m excited to share this information with you in case you’ve ever experienced hyperthyroidism or Graves’ disease, or know someone who has. If you have Hashimoto’s and hypothyroidism, this article will also be helpful to you, as it will give an overview of some root causes that may be present in both conditions, as well as some new protocols I’ve recently learned. 🙂

This article will provide insights relating to:

- Common threads and differences in Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s

- Fertility, pregnancy and thyroid status

- Pros and cons of conventional treatment for Graves’ disease

- Common root causes shared with Hashimoto’s and unique to Graves’ disease

- Thyroid eye disease

- Protocols for stabilizing thyroid hormones

Common Threads with Graves’ Disease and Hashimoto’s

Both Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s are autoimmune disorders in which the thyroid is attacked and destroyed by the body’s immune system. The difference lies in where the thyroid attack occurs and what antibodies are produced, that then carry out opposite physical effects relating to thyroid hormone production and the resulting symptoms.

In Graves’, the immune system attacks the thyroid stimulating hormone receptors (TSH-R) on the thyroid gland, causing TSH-R antibodies (also known as TSAb) to be formed, including thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) and TSH-binding inhibiting immunoglobulin (TBII). The increased levels of these antibodies inhibit TSH production, leading to increased thyroid hormone (T3 and T4) production and an overall stimulatory effect on the body (which can also stimulate and increase the thyroid’s size, causing a goiter or swollen thyroid gland).

TSI antibodies are elevated in more than 90 percent of those with Graves’ disease; they are also often elevated in people with thyroid cancer. TBII antibodies are elevated in more than half of people with Graves’ disease.

In comparison, in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, the immune system attacks different parts of the thyroid: either a protein of the thyroid called thyroglobulin, or thyroid peroxidase, an enzyme involved in thyroid hormone production. These attacks result in elevated thyroglobulin (TG) and/or thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies. These antibodies cause elevated TSH levels and a decrease in thyroid hormone (T3 and T4) production, leading to a metabolic slowdown in the body. TG antibodies are found in about 80-90 percent of people with Hashimoto’s; TPO antibodies in 90-100 percent.

Both autoimmune conditions are common causes of thyroid disease. Hashimoto’s is the most common cause of hypothyroidism in the United States (estimated to be responsible for about 90-95 percent of cases). Graves’ disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism in the United States, responsible for 60 to 80 percent of hyperthyroid cases. Other causes of hyperthyroidism include postpartum thyroiditis (I’ll talk more about this in a minute), overmedication of thyroid medication, toxic thyroid nodules, toxic multinodular goiters, subacute thyroiditis, and excessive iodine ingestion.

Graves’ disease is seven to eight times more common in women than men, and is most frequently seen in people ages 20 to 50 years. (1) Women are also at greater risk for having Hashimoto’s, with five to eight women affected for every one man. You can read my thoughts as to why women are more affected by autoimmune conditions (referred to as my Izabella Wentz Safety Theory) here.

A person’s risk factor for developing Graves’ disease increases if other family members have the disease, similar to what we see with Hashimoto’s. There have also been some genetic variants identified and associated with both of these conditions.

There is also another genetic predisposition that many autoimmune conditions seem to share. People with Graves’ (and Hashimoto’s, too) often have other autoimmune conditions themselves, or in their families. Some of these include celiac disease, rheumatoid arthritis, vitiligo, diabetes mellitus type 1, systemic sclerosis, myasthenia gravis, Sjögren’s syndrome, autoimmune adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease), and systemic lupus erythematosus. (2)

Having said that, we know from genetic studies with twins, that the cause for Graves’ is not solely genetic. There is certainly a genetic predisposition, but there are other factors as well. To give you an interesting perspective, my mom is an identical twin. She and her sister went to college in different cities, and my aunt developed Graves’ at some point during college, whereas my mom has never been affected by Graves’.

Most researchers believe that environmental triggers (as we see with Hashimoto’s, including viruses, infections, stress, food intolerances, and nutrient depletions) are the root cause of Graves’ disease.

I have also found that most people with Graves’ disease will have some form of intestinal permeability (which is one of the known requirements for having Hashimoto’s, based on both the research and my own clinical observations). Dr. Osansky and Dr. Zielsdorf have also found leaky gut to be quite common among their Graves’ patients. The great news here: even with a genetic predisposition present, we can do something about leaky gut and environmental triggers! People can get better by addressing these root causes.

Hypo/Hyper Fluctuations

Graves’ can sometimes evolve into Hashimoto’s and vice versa. There can also be fluctuations between the two conditions. When I was younger, I found that I had bouts of many of the classical symptoms of hyperthyroidism, including anxiety, palpitations, irritability, and menstrual disturbances. For those with Hashimoto’s, as the thyroid is destroyed, stored hormones can be released, causing sudden high levels of thyroid hormone. Then, as that is depleted and the thyroid becomes further damaged, thyroid levels can become low, with hypothyroidism redeveloping.

Additionally, someone may have Hashimoto’s but have a single thyrotoxic (producing too much thyroid hormone) nodule, resulting in hypo/hyperthyroid swings.

People with Graves’ can also transition to hypothyroidism over time. Approximately 15-20 percent of patients with Graves’ disease have been reported to have spontaneous hypothyroidism, thought to be due to the extended immune response of having Graves’ disease. (3) Additionally, people with Graves’ disease can experience transitions to hypothyroid states as a result of conventional treatment for Graves’ (which can render the thyroid useless).

Some clinicians believe that, in some cases, people may be (mis)diagnosed with Graves’ in the early stages of Hashimoto’s, simply because they had their labs done when the transient hyperthyroidism that occurs with Hashimoto’s (Hashi-toxicosis) was happening. I don’t have a lot of experience with clients who fit that parameter, but I do think this may be plausible and deserves more attention.

Now, let’s talk about how the classic symptoms differ between the two autoimmune conditions.

Symptoms of Graves’ Disease

People with Graves’ disease may experience one or more of the following symptoms:

Common Symptoms Associated with Graves’ Disease

- Irregular or rapid heartbeat, palpitations

- A fine tremor in the hands or fingers

- Anxiety or irritability

- Weight loss, despite normal eating habits (or even having an increased appetite)

- Heat sensitivity, hot flashes or increased perspiration

- Hair loss

- Muscle weakness

- Enlargement of the thyroid gland (goiter)

- Change in menstrual cycles (typically becoming lighter or irregular)

- Reduced libido

- Frequent or loose bowel movements

- Fatigue, yet difficulty with sleeping

- Separation of fingernails from the nail bed

- Increased risk of miscarriage

- Loss of calcium, leading to decreased bone density over time

- (Less commonly found) Graves’ dermopathy (the reddening and thickening of the skin, most often on the shins or the tops of the feet)

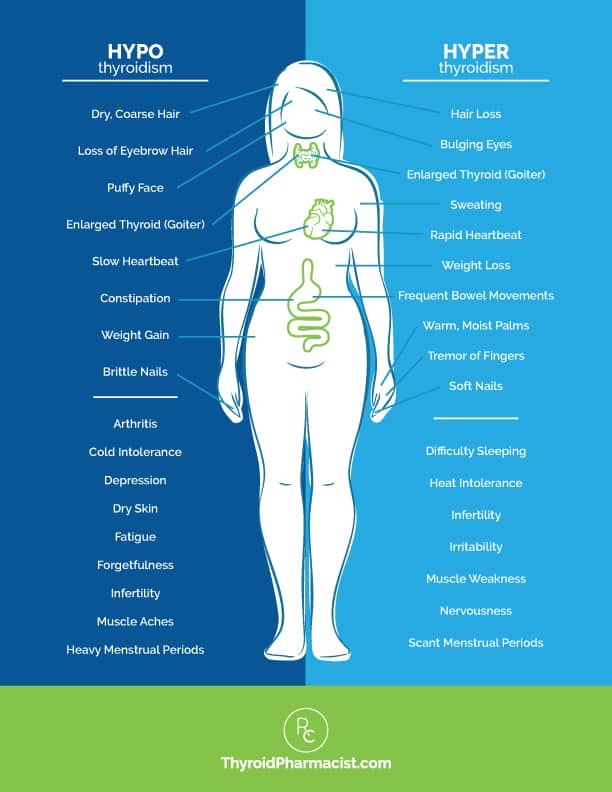

Here is a visual to help you compare the symptoms of hyperthyroidism with the common symptoms of hypothyroidism. Please note that it’s not uncommon for people to have symptoms from each side.

Another symptom associated with Graves’ disease is related to a condition involving the eyes. This is common enough that I’ll talk a bit more about it.

Graves’ Ophthalmopathy

Graves’ ophthalmopathy (or orbitopathy) is clinically seen in approximately 50 percent of patients with Graves’ disease, with severe forms affecting 3-5 percent of patients. (4)

This condition involves inflammation of the eyes, bulging of the eyes, and the swelling of the tissues around the eyes. Other symptoms can include:

- A gritty sensation in the eyes

- Retracted or puffy eyelids

- Inflamed or reddened eyes

- Pain or pressure in the eyes

- Sensitivity to light

- Double vision

- Diminished vision

Eye symptoms often occur within a window of about six months before, or six months after, the diagnosis of Graves’. While there is no known explanation for it, people with Graves’ who are also smokers tend to have more problems with their eyes than nonsmokers. Experts recommend that people with relatives with Graves’ disease, stop smoking as a preventative measure (along with getting an early diagnosis and treatment of any mild eye symptoms).

In more severe forms of Graves’ ophthalmopathy, there can be permanent vision damage if left untreated. The good news is that early treatment and normalizing thyroid hormone levels, which we’ll look into further on in this article, usually resolves conditions of the eyes related to Graves’ disease. I’ll share some helpful info on managing this later in this article.

Fertility, Pregnancy and Thyroid Issues

If left untreated, both Hashimoto’s and Graves’ disease can cause a number of health issues, including potential challenges with both fertility and pregnancy.

Infertility

We know from research that both Hashimoto’s and Graves’ disease can affect a woman’s (and man’s) fertility. This is because thyroid disease may interfere with sex hormone metabolism and a woman’s ovulation cycle (hyperthyroidism is often characterized by infrequent menstruation, light periods, or no menstruation). Infertility is a frequent concern of my clients as well as with the patients of our two experts.

The research also supports the connection. In one 2014 study that was conducted at the Endocrinology Clinic for Thyroid Autoimmune Diseases and involved 259 women, the prevalence of infertility in women was found to be 52.3 percent in women with Graves’ disease and 47 percent in Hashimoto’s (compared to about 10-15 percent of couples in the general population). (5)

Another fertility study I’ve seen for the general population, for comparative purposes, looked at women aged 15-49, and showed that 12.7 percent were found to have used infertility services. (6)

If this concern resonates with you, I’ll talk about Dr. Zielsdorf’s own unique approach to addressing infertility challenges later on in this article.

Pregnancy and Postpartum

It is estimated that Graves’ hyperthyroidism affects 0.2 percent of pregnant women. (7)

Studies have shown that immune function is suppressed during pregnancy, perhaps to allow the mother’s immune system to “tolerate” the developing baby. Sometimes, women who have not previously had thyroid issues, experience them during pregnancy — and in most cases, that resolves itself once the baby has been born.

A woman with hyperthyroidism may find that her symptoms increase in the first trimester, then subside, and then peak after delivery during the postpartum period. (8)

Maternal risks associated with Graves’ include increased incidence of miscarriage and pre-term delivery. A common issue for the mother is pre-eclampsia (high blood pressure associated with pregnancy). Fetal risks include the fetus developing hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism (thyroid antibodies may cross the placental barrier); however, this can often resolve itself once the baby is no longer exposed to the antibodies. There can be also other complications, such as an increase in fetal abnormalities.

The mother’s thyroid status (whether she previously received radioactive iodine therapy, had her thyroid removed, is on levothyroxine therapy, is taking anti-thyroid medication, etc.) can also affect both her and her fetus. (9) Methimazole (an anti-thyroid medication used in hyperthyroid treatment) is usually avoided during the initial trimester, due to side effects. (10, 11)

Careful monitoring and early counseling relating to risk factors is important for preventing such outcomes. I also like to see a mom stabilize her thyroid condition prior to conception if possible, by addressing her triggers and reducing her antibody levels. If natural treatment options and resolving underlying triggers (addressing a gut infection, removing a food sensitivity, etc.) reduce antibody levels, one can work with a practitioner to look at whether slowly changing the dosage of any anti-thyroid medications may make sense during one’s pregnancy.

So now let’s talk about how Graves’ disease can get diagnosed in the first place.

Diagnosing and Testing Graves’

Symptoms are often the initial clue, although some people with hyperthyroidism or Graves’ will not display traditional symptoms. Along with evaluating symptoms, the first thing practitioners will usually do is order lab work. A good functional practitioner will include either a full thyroid panel or an antibody test for TSI antibodies (thyroid stimulating immunoglobulins, the TSH receptor antibody that is the most common marker for Graves’). If a full thyroid panel is ordered, a practitioner will be looking for low TSH levels, elevated thyroid hormone levels (free T3, free T4), and TSI antibodies and TBII antibodies.

A person’s health history timeline is another important tool in root cause investigation and will help identify one’s genetic predisposition (a history of other family members with thyroid or other autoimmune conditions) as well as potential autoimmune triggers (such as infections, heavy metals, periods of stress and the like) that may increase one’s chances of having Graves’ disease.

Some doctors will do a radioactive iodine uptake test (RAIU) or uptake scan, which involves ingesting a small amount of radioactive iodine. If the iodine uptake is elevated, it points to having Graves’ disease.

I prefer to initially focus on testing for antibodies versus conducting the RAIU test, as TSH receptor antibodies are really the best measure of compromised immune system health and Graves’ disease. A positive test for antibodies is very conclusive (and does not require the radioactive iodine exposure, even if it is considered to be small). If the antibody test is negative (it is possible for someone with Graves’ to test negative for antibodies), but someone is still symptomatic, then I would suggest the RAIU test.

Some practitioners may also want to do a thyroid ultrasound, which uses sound waves to see changes in the thyroid, or growths. While you may not need an ultrasound to be diagnosed for Graves’ disease, in my practice, I generally recommend people get at least one ultrasound evaluation at some point during their treatment, especially for women of childbearing age. It can pick up things that may not yet be detectable in blood work, and is good baseline information to have.

Dr. Zielsdorf does recommend a thyroid ultrasound when a patient has a large goiter (as well as a full laboratory work up on the thyroid). She has found that many times, there will actually be no laboratory evidence of autoimmunity (antibodies), but evidence may be found by evaluating the echotexture (pattern of tissue layers) of the thyroid tissue on the ultrasound (a tell-tale sign of autoimmune thyroid disease).

Getting Lab Work Done

If your physician is not receptive to testing your antibodies (a simple blood test), you might want to find a functional practitioner.

While looking to find one, you also have the option of ordering your lab tests yourself through Ulta Lab Tests. They offer self-order options with discounted panels that I have already set up. These can be ordered anywhere in the U.S. You will receive a lab order that can be taken to a local lab. You may be able to self-order the labs and then send the receipts for reimbursement to your insurance. (Please check with your insurance to ensure that they will accept this, as well as to understand the required submission procedures.)

I recommend testing for both Graves’ and Hashimoto’s, by checking for TSH, free T3, T4, Hashimoto’s thyroid antibodies and TSH receptor (Graves’) antibodies, in case your symptoms are actually due to hyper/hypo swings with Hashimoto’s.

The TSH receptor antibodies test from Ulta Lab Tests will provide you with two biomarkers; one for the more commonly found TSI (Thyroid Stimulating Immunoglobulins), and one for the less common TBII (Thyrotropin-Binding Inhibiting Immunoglobulins) antibodies.

I’ll provide the reference ranges for TSI first, as it is more commonly elevated. Different labs may use slightly different reference ranges. Quest uses <140% as its reference range; Labcorp uses 0.00-0.55 IU/L. I always prefer to look for optimal ranges on lab work, which would be less than 0.55 IU/L or <80%.

The optimal TBII (Thyrotropin-Binding Inhibiting Immunoglobulins) reference range is 16-100 percent inhibition of TSH binding (Quest).

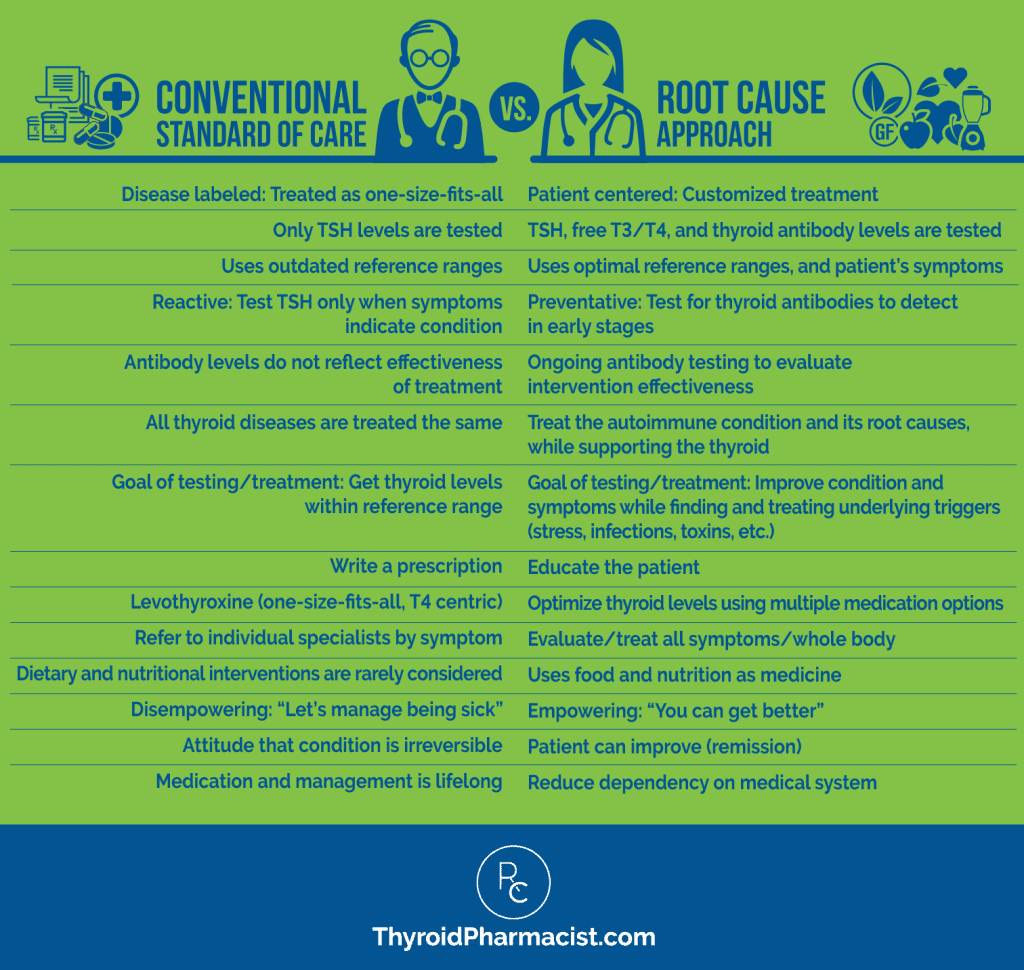

Once Graves’ is diagnosed, there are core differences between conventional treatment and a functional medicine or Root Cause approach to healing. Let’s first talk a bit about the three common treatments provided by conventional medical doctors. Then we’ll talk about addressing the common root causes of Graves’ using the Root Cause approach.

The Conventional Treatment for Graves’

The three traditional treatments for Graves’ disease include pharmaceutical options (anti-thyroid medications and beta-blockers), radioactive-iodine therapy, and thyroidectomy (surgical removal or partial removal of the thyroid).

Anti-thyroid medication may help control the symptoms of hyperthyroidism by lowering the amount of thyroid hormone that is produced, but will not cure the autoimmune condition of Graves’ disease. Thyroid damage will continue to occur. People often bounce between a state of remission and relapsing and becoming hyperthyroid again.

Beta-blockers (which lower blood pressure by causing the heart to beat more slowly) are sometimes used to address heart palpitations and other cardiac symptoms associated with hyperthyroidism, though they do not address thyroid or immune system health.

After a period of time, many doctors will then recommend radioactive iodine or surgery. These conventional treatments are irreversible thyroid treatments that will cause permanent hypothyroidism.

Unfortunately, while this is touted as a “cure” for hyperthyroidism by conventional medicine, this is like throwing out the baby with the bathwater. While the thyroid may be the target of the immune system, in many cases, it is not the root cause of the autoimmune attack, and the immune system will find another place to attack. Unfortunately, I have seen too many people with additional autoimmune conditions after having their thyroid removed or treated with radioactive iodine. For some particular reason, rheumatoid arthritis seems to be the most common autoimmune condition reported by my clients.

Additionally, if you’ve seen The Thyroid Secret, you may have heard Dr. Zielsdorf’s note that nearly every cell in the body requires thyroid hormone, and the decision to undergo an irreversible thyroid treatment is not the best option, unless truly necessary. While conventional medical doctors will say that people just need to take thyroid hormones after these treatments, as a pharmacist specializing in optimizing thyroid hormones, I can tell you that many people are not managed properly with thyroid hormones and suffer needlessly with symptoms of under- and over-medication. Dr. Zielsdorf has found that her thyroid patients, post RAI and post-thyroidectomy, often need different dosing and medication protocols compared to the average person, but, unfortunately, many physicians are not aware of this.

Let’s talk a bit more about the pitfalls associated with these three conventional treatments.

1. Anti-thyroid medications and beta blockers: Anti-thyroid medications are usually given until thyroid levels stabilize. Typically, a person with hyperthyroidism will need to take medications for 12-18 months. Methimazole (Tapazole®) is usually prescribed, but also propylthiouracil (PTU). Even when thyroid hormone levels stabilize, discontinuation of anti-thyroid drugs is followed by 50 percent recurrences within four years.

In one research study, when people were assessed at a 20-year follow-up, about 62 percent had experienced recurrent hyperthyroidism, 8 percent had subclinical hypothyroidism, and 3 percent had overt hypothyroidism (based on levels of antibodies). Only 27 percent were still in remission from hyperthyroidism (based on symptoms). (12)

There is also a risk of side effects, such as liver damage or significantly depressed white blood cell count, as well as a number of other side effects and drug interactions. Furthermore, some people just don’t feel well on these medications, and methimazole is contraindicated during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Beta blockers, such as propranolol (Inderal), also have side effects such as blocking the production of CoQ10 (an antioxidant that helps generate energy). As such, the use of beta blockers and anti-thyroid medications need to be monitored by a physician. I would also recommend working with a functional medicine specialist to see which nutrients may need to be restored while taking these medications.

2. Radioactive iodine therapy: This treatment permanently destroys the cells of the thyroid gland so that it no longer produces a surplus of thyroid hormone. The thinking seems to be that the resulting hypothyroidism is easier to manage than hyperthyroidism. But, this treatment does nothing to address the immune system and introduces other concerns, including risks associated with the exposure to radioactive iodine itself.

As Dr. Osansky reminds us, when a person receives radioactive iodine, they aren’t sent home to return to normal life right away. Many will be quarantined for a period of time, and, even after being sent home, will have to keep their distance from others. Women will be told not to become pregnant for several months, as the effects of the radioactive treatment may affect a developing fetus.

Numerous studies have shown that radioactive iodine therapy is associated with an increased risk of thyroid eye disease as well. (13) One study found that Graves’ ophthalmopathy may occur after radioactive iodine therapy, in approximately 15 percent of patients. (14)

I’ve seen people who had Graves’ disease and who have had radioactive iodine therapy. They had taken their thyroid medications, but a few years down the road, they developed another type of autoimmune condition. Why? Because their compromised immune systems were never addressed. Often, individuals who share similar outcomes may then undergo surgery (which again does not address the underlying immune condition).

3. Thyroidectomy/Surgery: Surgery is often the conventional treatment for pregnant or lactating women, for those with ophthalmopathy (again due to radioactive iodine potentially worsening that condition), for those with large goiters, or for those continuing to have hyperthyroidism after anti-thyroid drug therapy and/or radioactive iodine treatment.

The surgery itself can have risks, including possible damage to the parathyroid gland (that can impact a patient’s ongoing calcium levels) or damage to the laryngeal nerve (which can impact swallowing and impair speech).

A doctor may recommend a partial thyroidectomy (subtotal thyroidectomy), which may allow enough of the thyroid function to remain to decrease the need for hypothyroid hormone replacement — but in such a case, there is a risk for ongoing hyperthyroidism recurrence. (15)

Again, the important point is how this leaves a patient. When Dr. Zielsdorf spoke about this common conventional treatment option in my interview with her for my Thyroid Secret documentary, she mentioned how heartbreaking it was to see a patient who had their thyroid removed and was told that they would be “fine.” In fact, their lives were irreversibly changed, as the thyroid is the metabolic source for the entire body.

While functional practitioners may consider using anti-thyroid medications or beta-blockers as a temporary measure to address symptoms (especially dangerous cardiac symptoms), we know that in order to fully resolve Graves’, we must resolve the underlying autoimmune condition. In order to do that, we must identify a person’s root cause triggers.

Common Root Causes and a Functional Approach

When presented with a patient or client suspected of having Graves’ disease, rather than focusing solely on the thyroid dysfunction, functional medicine practitioners (and I as a Root Cause detective) focus on restoring the health of the immune system. Only this will stop the TSI antibodies from attacking the TSH receptors, which in turn will prevent the excess production of thyroid hormone.

As I mentioned earlier, Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s actually share many of the same root cause triggers. Thus, functional practitioners approach both the same way, identifying and removing the triggers (such as an infection or stress) and restoring any compromised areas of the body (such as healing the gut or adrenals).

Here’s a good graphic which depicts the differences in the conventional and Root Cause approach:

Common Root Causes for Graves’

The list of common root causes for Graves’ looks similar to the one for Hashimoto’s. The good news is that I have a lot of detailed information and natural treatment recommendations in both of my books, Hashimoto’s Protocol and Hashimoto’s: The Root Cause.

Although Graves’ disease does have a genetic component, remember what I always say: “Our genes are not our destiny!” Twin studies suggest that genetic factors explain about 79 percent of the incidence of the condition, while environmental factors (that we have control of!) explain the other 21 percent. (For Hashimoto’s, based on my clients and readers, I’d say the genetic component is more like 25 percent and the environmental factors, closer to 75 percent.)

To further underscore this point, a study evaluating risk factors in spouses (presumably with no genetic link!) showed that the risk for Graves’ increases among spouses by 2.75 percent. (16)

Clearly other contributing factors are at play, and some of the commonly reported ones specific to Graves’ disease are infections, stress, an excess of iodine, food intolerances (gluten in particular), tobacco use, and the use of certain drugs (interferon-alfa, amiodarone, and CD52 mAbs). As I already mentioned, I’m always fascinated to see the health differences in my mom and my aunt, who are identical twins, one who had Graves’ in her 20’s (now in remission), one who did not!

A functional practitioner will search for a given patient’s unique set of autoimmune triggers by taking a thorough medical history and doing the appropriate lab work. In my own practice, along with documenting known health history and family health history data, I ask clients to think about the last time they felt well, as well as document what was going on in their life at that time, and right before. Many times we will find a particular event, such as a stressful period or seemingly unrelated illness (like the mono many of us had in college).

I loved getting nerdy with Dr. Osansky and Dr. Zielsdorf and comparing notes on the common root causes they see in their medical practices.

Dr. Osansky sees chronic stress as a major trigger, along with food intolerances and infections. He also believes environmental toxins are a big underlying trigger and is one we don’t even know a lot about, given that chemicals are tested for toxicity in isolation. For example, BPA is studied, and separately, mercury may be studied. But what about exposure to both of these (and other) toxins together, over the course of a lifetime? People are not just exposed to one environmental toxin, and we don’t really know how they interact when combined, nor how that impacts thyroid health.

In talking with Dr. Sarah Zielsdorf, she finds autoimmune diseases tend to have the following underlying triggers: pathogens (parasites, viruses, bacteria, yeast/mold — you name it), underlying biotoxins/mycotoxins from said infections, heavy metals, and thyroid halide toxicity (excess exposure to bromide, chloride, and fluoride, which displace iodine); and that too little or too much iodine can be bad for autoimmune thyroid disease.

She has also found in her own practice that females are more predisposed to Graves’ disease with precipitating or causal factors, including genetics, pregnancy, physical/emotional trauma, acute or chronic infections, environmental toxins, and food antigens. I have seen this in Hashimoto’s as well (thus my earlier mentioned Izabella Wentz Safety Theory).

For me, it’s always interesting to think about the individual root causes, as well as the overall picture with the overall load of triggers. I don’t think it’s just one thing for most people. I think it’s a buildup of different things that causes our systems to get overwhelmed. In my early days of being a root cause detective, I was passionate about finding every single cause. This led to a lot of time and money spent on lab testing.

However, with experience, I’ve found that often symptoms can be diminished, and sometimes autoimmune conditions can be put into remission, by supporting three major body systems (the liver, adrenals, and gut), reducing the load of triggers that overwhelms the body. In working and speaking with other clinicians, it’s been quite an interesting journey to see that there’s often more than one way to skin a cat… Some practitioners may focus deeply on toxins; others will do more deep work with infections or with diet; others will incorporate immune balancing protocols… and they will all get great results. I like to keep an open mind to the many protocols that can help people.

So, while we talk about the many potential triggers, I do want to point out that we may not always need to find every single trigger in an individual to feel better, and sometimes just baby steps can make a world of a difference, such as starting with the common issues of food intolerances and stress.

Diet and Food Intolerances

In Hashimoto’s, we know from the research that the three requirements to have autoimmunity are: a genetic predisposition, one or more triggers, and intestinal permeability. In Graves’, we see similar requirements, although the intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”) piece may not always be as apparent. With that said, however, it is very common, and it is often related to food intolerances such as sensitivity to gluten.

If someone is sensitive to gluten, consuming it can inflame the intestinal lining, which can then lead to intestinal permeability. This is a very inflammatory condition that also impacts nutrient absorption and our body’s ability to fight off infections. It can also be a trigger for many conditions of autoimmunity.

Removing gluten in these cases can result in less inflammation, improved immune system health, and improved thyroid hormone (and antibody) levels.

We know from the research and the results of my survey from 2,232 of my readers with Hashimoto’s, that most people with autoimmune thyroid conditions feel better when gluten free. (In my survey, 88 percent of people with Hashimoto’s who became gluten free felt better.)

Just like most functional medicine practitioners and I advocate, both Dr. Zielsdorf and Dr. Osansky will typically have their patients focus on dietary changes as an initial step in their healing. It is an easy, natural first step that can have fairly immediate results, and can also be done at home, by the individual, without needing a specialist or an expensive test.

Dr. Osansky will usually have his patients follow a strict Autoimmune Paleo diet (AIP) for the first month, and then he will see how they’re doing. If they are struggling with the more restrictive AIP diet, he may allow them to slowly reintroduce foods, maybe even transitioning them to the less restrictive standard Paleo diet.

Dr. Osansky adds that a person’s diet needs to be right for them and not add a lot of stress, as stress can be a trigger, too. Thus, he adjusts diet recommendations based on the individual.

Dr. Zielsdorf also initially puts patients on an oligoantigenic elimination diet (a diet that limits the foods eaten to a very narrow list of foods that are not likely to cause reactions), which usually follows the Autoimmune Paleo template. The goal is to down-regulate their gut inflammation. She’ll also look for co-infections and other potential triggers before identifying a treatment plan (which may include Low-Dose Naltrexone, which I’ll talk about in a moment).

In my own clinical practice, I also often recommend the AIP or Paleo diets, as these diets remove the chief offending foods, but I’ve often found that those who are already clean eaters need deeper work in the realm of gut infections. By focusing on nutrients, the liver, the adrenals, and the gut, clients are able to introduce foods quicker than just doing the diet alone.

Stress

Stress and adrenal dysfunction are common triggers I see in treating my Hashimoto’s clients.

Dr. Osansky also sees a lot of Graves’ patients who have these issues, and he feels that many people don’t focus enough on the importance of adrenal health and stress management. At the time he was diagnosed with Graves’, he himself had been surprised to find that stress was a big issue for him.

He noted that he thought that he did a good job of handling stress, but when he saw the results of his adrenal testing, he realized that wasn’t the case. He urges clients to work on their stress-handling skills and doing things to try to reduce stress levels.

Stress can be a factor with Graves’ in a few different ways, including causing dysregulation of the immune system, an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines (a factor with all autoimmune conditions), and a decrease in secretory IgA, which serves as a form of protection (it lines the mucosal surfaces of the gastrointestinal tract, forming a barrier of sorts). Researchers have noted that having low secretory IgA levels can make someone more susceptible to an infection (such as H. pylori), food allergens, or similar autoimmune trigger.

There are studies that have shown that stress affects a patient’s ability to achieve a euthyroid (normal thyroid gland function) state after the start of anti-thyroid medications; those experiencing stress took longer to gain euthyroid status.

Another study focused on patients with a previous history of stress versus those with no such history. The study found that patients treated with radioactive iodine therapy became hypothyroid earlier when having a previous history of stress. (19) Researchers proposed this was due to the autoimmunity being stress-induced in the first place. Another study focused on the use of anti-thyroid medications, exposure to stress, and potential hyperthyroidism relapse, and found stress had a definite negative effect. (20)

Another type of stress that impacts thyroid disorders is physical stress, in the form of exercise. For people with Graves’ disease whose thyroid hormones are well above the optimal range, exercise can “overheat” the body in a dangerous way. In some ways, it’s as if their bodies are already running on a treadmill, all day and night. Adding excessive exercise on top of this puts a great deal of stress on the body and can cause a patient to go into heart failure. My recommendations for exercise with Graves’ disease are similar as for those with Hashimoto’s and adrenal issues — focus on stress reducing and nurturing activities, such as walking and yoga, until your hormones are stabilized and you are better equipped to handle the stress of more vigorous forms of exercise.

For more information about stress and your adrenals, and how stress can be a trigger for autoimmunity, please see my previous article. This article also talks about how you can test your stress response, as well as natural ways to nurture your adrenals.

I’d like to note however, that while most adrenal adaptogens are safe for people with Hashimoto’s, I do recommend additional caution in using them with Graves’.

Helicobacter Pylori Infections

I often get excited when I find certain infections in my clients… This is because I know that treating the infection can result in symptom improvement and sometimes even a quicker remision. One of the infections I get most excited about in Graves’ disease is H. pylori. Research has shown a positive correlation between H. pylori infections and autoimmune thyroid diseases, including Graves’. A 2013 Chinese study found a rate of H. pylori infection in 66 percent of people with Graves’ disease and 37.7 percent of people with Hashimoto’s.

Dr. Osansky shared with me that H. pylori infections are one of the more common root causes he sees in his patients with Graves’. He has had people go into remission from Graves’ by eradicating the infection, when that was their sole trigger. Many times, just as in Hashimoto’s, there may be more than one trigger. H. pylori can cause other issues that can themselves become autoimmune triggers; it can contribute to low stomach acid, for example. When people have low stomach acid, their foods may not be adequately digested, which can end up causing food sensitivities.

In one 2017 review of existing literature, 139 articles discussed the association between H. pylori and autoimmune thyroid diseases. Although definite associations were found, it is difficult to determine whether the H. pylori always triggered the autoimmunity, or whether the autoimmune condition made someone more susceptible to the H. pylori infection by weakening the immune system (kind of a “chicken or the egg?” thing). In the same study, researchers did observe that eradication of the infection reduced levels of thyroid antibodies in patients with both Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s. (21, 22)

Because H. pylori is found in so many people with Graves’ disease, it is worth evaluating for infection; if not the original trigger for autoimmunity, it certainly isn’t helping an individual’s overall immune system health.

This type of infection is also an example of where a functional practitioner may choose to use a combination of both conventional and natural treatment methods to address a particular root cause. I know that Dr. Osansky, for example, has found that H. pylori is challenging enough to eradicate, that antibiotics may be required along with natural treatments, such as cleaning up one’s diet (minimizing sugars and refined foods), using probiotics to replenish one’s healthy gut bacteria, and taking herbs that can help eradicate the infection (such as garlic, turmeric, and thyme).

In 2015, 80 percent of my clients who hit a plateau with diet and nutrition interventions and took the gut tests I recommended, tested positive for at least one gut infection. For more info, including testing and natural treatment options I have found helpful for H. pylori, please see my full article on H. pylori. Remember that we are treating the root cause, so whether you have Graves’ or Hashimoto’s, these protocols can be helpful in identifying and resolving the infection.

Epstein Barr Virus (EBV)

Epstein-Barr (EBV) is a virus that causes mononucleosis (“mono”), a debilitating viral infection that is very contagious and common among college students (as well as 95 percent of the general population!). While having the virus (which can remain dormant throughout your life) doesn’t mean you’ll be triggered into an autoimmune condition, the reactivation of the virus can be a trigger. This particular reactivated virus was one of the root causes that I personally had to deal with in my Hashimoto’s journey.

In her clinic, Dr. Zielsdorf has found that patients with the largest goiters (often multinodular, sometimes referred to as swollen gland) and those with Graves’ disease, often have evidence of a reactivated Epstein-Barr infection. This is purely anecdotal in her Midwestern clinic, but she sees many patients with elevated titers of Early Antigen antibodies for EBV, which may reflect a reactivated virus in a genetically susceptible patient. She has found that if a patient is not getting better on their treatment plan, it may often be due to a co-infection.

According to Dr. Zielsdorf, Epstein Barr Virus (EBV), or human herpesvirus-4, is one of many viruses (Hepatitis C virus, Cytomegalovirus, HSV 1+2, influenza, among others) that are known to trigger autoimmunity via molecular mimicry, among other mechanisms. Other bacterial agents, including Streptococci, Staphylococci, Yersinia, and Helicobacter pylori, may also play a role.

In a 2015 Polish study, the Epstein-Barr virus was found in the thyroid cells of 62 percent of people with Graves’ and 80 percent of people with Hashimoto’s, while controls did not have EBV present in their thyroid cells.

Other research shows connections between EBV and autoimmune thyroid conditions as well. (23, 24, 25) There have also been correlations found between increased EBV activation with other autoimmune conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis. (26)

A more recent study published in October 2018 showed that Epstein-Barr reactivation resulted in the production of thyrotropin receptor antibodies, which are associated with Graves’ disease. (27)

You can read more about EBV and the autoimmune thyroid connection, diagnosis and testing information, and natural treatment options. Remember, we don’t just want to focus on eradicating infections — we also need to ensure we are always working to improve our overall immune health. A functional practitioner will also ask why a person has the EBV reactivation in the first place (not everyone with an infection has a reactivation or autoimmune response). Other triggers, such as stress or environmental toxins, may be making a person more susceptible to an EBV infection.

Now I’m going to switch gears a bit and provide some additional “gems” from both experts relating to their approach to treating Graves’ disease. I’ll also provide info on how you can connect with them and access some great resources they have.

Additional Treatment Options

Beyond addressing diet, supporting adrenal health, and eradicating underlying infections, there are some additional treatments that have worked well for the doctors I interviewed in treating their patients with Graves’ disease and their challenges with it.

Many of these treatments involve adding supplements to your regimen. Please note, however, there are some supplements to avoid, as they can stimulate hyperthyroidism! These include ashwagandha, bladderwrack, caffeine (including green tea and ginseng), and certain over-the-counter products designed to increase focus and energy.

Now onto some that can be helpful and should not exacerbate Graves’!

Low Dose Naltrexone (LDN) as a Critical Therapy

Dr. Zielsdorf is one of the only doctors that I know of in her region that treats patients with Graves’ disease early-on with LDN (if they don’t have Graves’ ophthalmopathy or extreme symptoms where they have to be hospitalized).

She shared with me that Low Dose Naltrexone (LDN) and dietary modifications (an anti-inflammatory, oligoantigenic diet), along with treatment of underlying triggers, are her first choice initial therapies for Graves’ disease. LDN is an immuno-modulatory agent, which can help in the autoimmune response by balancing the immune system and decreasing inflammation. Dr. Zielsdorf uses compounded LDN, dosed between 0.5-4.5 mg and given at night, for patients with Graves’ disease.

The mechanism of action for LDN is that it temporarily blocks opioid receptors in the Central Nervous System (CNS). When it unblocks, there is an increase in beta-endorphins and met-enkephalins (also known as opioid-derived growth factor — OGF). Increased endorphins help with mood, sleep, and pain — all common with autoimmunity.

Met-enkephalins work by reducing inflammation and help heal intestinal epithelial cells. Since there are receptors for OGF on the thyroid (OGFr), this may help explain why LDN helps Graves’ patients — by regulating abnormal cell growth. LDN is also an antagonist of non-opioid receptors, called Toll-Like Receptors (TLR-4 and TLR-9), which reduce cytokines and other inflammatory signal molecules.

This process does take time, and Dr. Zielsdorf often uses these treatments alongside a patient’s hyperthyroid medication (beta blockers and methimazole among others), while closely monitoring them so that medications can be reduced.

She has had many patients wean off their antithyroid drugs, or, if in the beginning stages of Graves’ disease, normalize their thyroid numbers, eliminate antibody production, and reduce their goiter size.

I find this info so exciting. I, too, have used LDN in my practice with good success (and have even used it myself).

Low Dose Naltrexone for Infertility and Pregnancy

I asked Dr. Zielsdorf about the issue of infertility in her patients having Graves’ disease. Her typical approach is to focus on removing the offending autoimmune triggers, but she is also a proponent of using Low Dose Naltrexone (LDN) in this instance as well. She likes using LDN and has found it to be very safe (for pre-pregnancy stages, as well as during pregnancy, breast-feeding and postpartum), though it isn’t yet FDA approved for expecting mothers.

Dr. Zielsdorf told me a story about an interview she had heard given by a fertility specialist; he had anecdotally recounted that he had seen a 15 percent increase in pregnancy of some of his patients with autoimmune disease and infertility issues, just by taking LDN.

Dr. Zielsdorf also shared that these pregnancies were occurring without the use of common fertility treatments, such as Clomid (a prescription drug for infertility that has a number of side effects), IVF (in vitro fertilization), or IUI (intrauterine insemination). Instead, her patients used LDN, which is cheap, non-toxic, and can be compounded to be gluten and dairy-free. Additionally, it is easy to take and has a very low side effect profile, so it is one tool that Dr. Zielsdorf uses to specifically counteract the inflammation that is thought to be the driver behind infertility. I’ve also found LDN to be a helpful tool for fertility with Hashimoto’s.

Balancing Thyroid Hormones with Three Healing Herbs

A key difference between the functional medicine approaches to Graves’ and Hashimoto’s is that in Hashimoto’s and hypothyroidism, our goal is to increase thyroid hormones. In Graves’ disease and hyperthyroidism, we want to decrease them. In Hashimoto’s, we use thyroid hormones that are bioidentical; while in Graves’, thyroid blockers are needed.

In conventional medicine, thyroid blocking medications would be used. However, there are several herbs that also function as thyroid blockers. Dr. Zielsdorf and Dr. Osansky say that some work well enough, that sometimes medications can be spared or minimized, and the thyroid gland may be saved.

Dr. Osansky has three favorite herbs that he frequently recommends:

- Bugleweed: When he was dealing with his own Graves’ condition, one of the herbs that really helped him was bugleweed, and it’s one that his patients also commonly take. It’s an herb with anti-thyroid activity, so it helps many people to lower their thyroid hormone levels. Bugleweed is rich in lithospermic acid, an organic acid that decreases levels of both T4 (the storage form of thyroid hormone) and T3 (the active form). Importantly for those with Graves’, it also prevents thyroid antibodies from binding to the thyroid. Precautions: Bugleweed is not safe to take during pregnancy and breastfeeding because of its effect on hormones. Those with diabetes should monitor their blood sugar levels closely, as it may lower levels.

- Motherwort: This member of the mint family alleviates symptoms such as heart palpitations, anxiety, sleeplessness, and reduced appetite. Motherwort is used more for the cardiac symptoms seen in Graves’, as a natural beta blocker. It is not as powerful as a true beta blocker, but it also doesn’t have many of the side effects associated with them. Precautions: Motherwort has been known to cause miscarriages, increase uterine bleeding, and potentially interact with cardiac medications, so be sure to check with your doctor before taking it.

- Lemon balm: This herb is also a member of the mint family and appears to block hormone receptors, preventing TSH from binding to thyroid tissue and keeping antibodies from attaching to the thyroid. Thus, it helps to calm thyroid symptoms by reducing stress and anxiety, improving sleep and appetite, and easing pain. Precautions: When taken in large doses, lemon balm has been known to cause headaches, painful urination, increased body temperature, nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, dizziness, and wheezing. It might lower blood sugar levels in people with diabetes.

I was excited that both Dr. Zielsdorf and Dr. Osansky had the same three top herbal choices. Dr. Zielsdorf has found the Herb Pharm Thyroid Calming formula that contains all three herbs, to help her patients with symptoms of palpitations, fatigue, and anxiety, and has also seen improved hyperthyroid thyroid labs with its use. She doesn’t use this in isolation, but may use it with other treatments for hyperthyroidism, along with lifestyle modifications (such as the elimination of gluten).

How Glutathione Can Help

Dr Zielsdorf also really likes to use topical glutathione over the thyroid for patients with thyroiditis/goiter (swollen thyroid), which can help ease symptoms related to difficulty with swallowing. Her first choice has been Apex Energetics Super Oxicell, or Oxicell SE (for those with sensitive skin). She also recommends Xymogen Glutathione Plus topical cream.

And while on the topic of the antioxidant glutathione, Dr. Osansky likes to proactively focus on addressing glutathione depletions in his patients, as healthy glutathione levels can support liver function and increase the clearance of toxins, such as mercury, from the body. He also encourages the consumption of foods which can increase glutathione levels, such as garlic, kale and broccoli.

Glutathione can be taken orally as well, and NAC is a supplement that can help with increasing glutathione levels. Selenium is a supplement Dr. Osansky likes to use to support glutathione production, and it also has numerous thyroid benefits.

The Benefits of Selenium

I recommend selenium as one of the most important supplements for Hashimoto’s, and studies have shown it to have similar benefits for postpartum thyroiditis, and hyperthyroidism.

One study, performed to assess the effects of L-carnitine and selenium in the management of symptoms and endocrine profile in patients affected by subclinical hyperthyroidism, recruited patients with TSH levels between 0.1-0.4 mIU/L, and positive antibodies. The participants received one tablet containing 500 mg of L-carnitine and 83 mcg of selenium daily, for one month. The primary outcome was the improvement of the quality of life with the disappearance of main symptoms associated with hyperthyroidism. After treatment, participants reported more than a 50 percent drop in symptoms, while thyroid hormones and antibodies remained within the normal range. (32)

Selenium for Graves’ Orbitopathy

Thyroid eye disease (TED) is an inflammatory orbitopathy with significant impact on visual function and quality of life. As mentioned above, in the case of hyperthyroidism, it is referred to as Graves’ orbitopathy.

A meta review of treatments used to manage Graves’ orbitopathy showed that selenium is an effective therapy for those with milder forms of the disease. (33) On the other hand, radioactive iodine ablation of the thyroid has been shown to make this condition worse in many patients!

It is known that oxygen free radicals and cytokines play a pathogenic role in Graves’ orbitopathy, therefore the antioxidant effect of selenium is thought to be the reason for its effectiveness in treating the condition.

Another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial split their trial group of 159 patients with mild Graves’ orbitopathy, into two groups. One received selenium (100 μg twice daily), while the second was given pentoxifylline (an anti-inflammatory agent) at a dose of 600 mg twice daily, or a placebo (twice daily) orally, for six months. They were then followed for six months after treatment was withdrawn. At the six-month evaluation, treatment with selenium, but not with pentoxifylline, was associated with an improved quality of life, and slower progression of the disease as compared with the placebo group. (34)

Additionally, low serum vitamin D is associated with thyroid eye disease, and preliminary research indicates that supplementing vitamin D may be an important part of managing the condition. (35)

Using Carnitine to Modulate Thyroid Function

L-carnitine is another supplement that has been shown to help manage the symptoms associated with hyperthyroidism and Graves’ disease. Carnitine is a nitrogen-containing compound that is necessary for the transport of long-chain fatty acids into the mitochondria for oxidation. When a person is in a state of hyperthyroidism, they will lose carnitine through their urine, requiring it to be replaced in the body.

Dr. Osansky states that L-carnitine can help with hyperthyroidism by inhibiting thyroid hormone, thereby reducing cardiac symptoms associated with these conditions, such as high pulse rate and/or palpitations. (37)

He frequently prescribes carnitine supplements to his patients, with doses varying based on other medications or herbs the patient is using. For example, a patient using an anti-thyroid medication or herb will use a lower dosage, while a person who is not taking these medications or supplements might take a dose as high as 4 grams per day.

Carnitine supplementation has also been shown to help address muscle weakness, which is common in both hyper- and hypothyroidism. Skeletal muscle L-carnitine is thought to play a role in muscle weakness in these groups, as studies have shown abnormal levels of carnitine in serum and urine of patients with thyroid dysfunction. In skeletal muscle samples obtained for carnitine analysis from control subjects, there was a significant reduction in carnitine found in the sample from hyperthyroid individuals, with a return to normal as normal thyroid function was regained. (36)

Further studies have shown that L-carnitine is effective in both reversing and preventing symptoms of hyperthyroidism, and has a beneficial effect on bone mineralization. (38) It also had a protective effect against oxidative stress on the liver of hyperthyroid rats. (39)

Maintaining enough L-carnitine in the body can help prevent or reverse many of the symptoms associated with hyperthyroidism, including insomnia, nervousness, and tremors, in addition to muscle weakness and heart issues. (Learn more about carnitine here.)

Limbic System and Autonomic Nervous System Reset

Another gem from Dr. Zielsdorf is related to limbic system impairment.

The limbic system is the part of the brain that includes the hippocampus and amygdala, the seat of motivation, emotion, learning, and memory.

What Dr. Zielsdorf has found is that a person’s limbic system can become impaired, and they can get stuck in a “trauma loop” secondary to chronic illness. When this happens, a person may not be able to heal while in this state. She suspects limbic system impairment when a patient has sensitivity to supplements and medications, is extremely chemically sensitive, has oral tolerance issues (and may be down to half a dozen foods they can eat), or has paradoxical reactions to medications or other treatments. She has started using limbic system reset programs in these cases, prior to implementing other treatment plans.

Research has found that patients with hyperthyroidism may suffer from frontal cortex and limbic system metabolic disorders, as well as dopamine dysfunction. (28) Functional brain imaging has shown a relationship between thyroid function, mood modulation, and behavior. Many of the limbic system structures within the brain with thyroid hormone receptors, have been linked to the pathogenesis of mood disorders and a multitude of effects on the central nervous system. (29)

While talking about the central nervous system, Dr. Zielsdorf has noted the importance of correcting autonomic nervous system dysregulation, as this imbalance and resulting parasympathetic nervous system weakness causes less “rest and digest,” and too much sympathetic nervous system activation, or “fight or flight.” The problem lies in decreased vagal nerve tone, which can be helped by improving the function of this nerve. The vagus nerve is known as the “wandering nerve,” as it seems to innervate much of our viscera, and is the longest of the twelve cranial nerves. The gut microbiome influences the nervous system and immune system via the vagus nerve (something we are just starting to learn about in exciting research), and we now know that in order to heal an inflamed gut, we must work on balancing the autonomic nervous system.

Final Thoughts on Graves’ Disease and Hyperthyroidism

If you or a loved one has been diagnosed with Graves’ disease, or if you suspect you may have the condition, you’ll want to work with a functional practitioner who has been trained to resolve the root causes for the autoimmune condition. With hyperthyroidism, you will want to have the guidance of someone knowledgeable given the unique cardiac symptoms you could experience.

While finding a practitioner, you can easily embark on dietary changes today by removing possible food sensitivities and embarking on a Paleo or AIP style diet. You can also start to reduce environmental toxins in your food, home and life. Improving your stress management can also support a healthier immune system and thyroid.

As always, I wish you well on your journey toward better health!

P.S. You can download a free Thyroid Diet Guide, 10 thyroid friendly recipes, and the Nutrient Depletions and Digestion chapter from my first book for free by signing up for my weekly newsletter. You will also receive occasional updates about new research, resources, giveaways and helpful information. And, for future updates, make sure to follow us on Facebook!

References

- Graves’ Disease. Medscape Emedicine website. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/120619-overview#a6. Updated March 2018. Accessed December 19, 2019.

- Zielsdorf S. Graves’ Disease. Presented at the LDN AIIC Conference, June 2019 in Portland, OR. https://www.ldnresearchtrust.org/conference-2019/graves-disease. Accessed January 12, 2020.

- Umar H, Muallima N, Adam JM, et al. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis following Graves’ disease. Acta Med Indones. 2010 Jan;42(1):31-5.

- Wiersinga WM, Bartalena L. Epidemiology and prevention of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid. 2002 Oct;12(10):855-60.

- Quintino-Moro A, Zantut-Wittmann DE, Tambascia M, et al. High prevalence of infertility among women with Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014:982705.

- Infertility. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated July 15, 2016.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/infertility.htm. Accessed Jan 13, 2020.

- Nguyen CT, Sasso EB, Barton L, et al. Graves’ hyperthyroidism in pregnancy: a clinical review. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;4:4.

- Andersen SL et al. Hyperthyroidism incidence fluctuates widely in and around pregnancy and is at variance with some other autoimmune diseases: A Danish population based study. J. Clin. Endocrinol Metab. 100: 1164-1171. 2015.

- Lazarus JH. Pre-conception counselling in graves’ disease. Eur Thyroid J. 2012;1(1):24–29. doi:10.1159/000336102

- Gude D. Thyroid and its indispensability in fertility. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2011;4(1):59–60.

- Quintino-Moro A, Zantut-Wittmann DE, Tambascia M, et al. High prevalence of infertility among women with Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014:982705.

- Wiersinga WM. Graves’ disease: can it be cured?. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2019;34(1):29–38.

- Ponto KA, Zang S, Kahaly GJ. The tale of radioiodine and Graves’ orbitopathy. Thyroid. 2010 Jul;20(7):785-93.

- Vannucchi G, Campi I, Covelli D, et al.Graves’ orbitopathy activation after radioactive iodine therapy with and without steroid prophylaxis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Sep;94(9):3381-6.

- Smithson M, Asban A, Miller J, et al. Considerations for thyroidectomy as treatment for Graves Disease. Clin Med Insights Endocrinol Diabetes. 2019;12:1179551419844523.

- Płoski R, Szymański K, Bednarczuk T. The genetic basis of graves’ disease. Curr Genomics. 2011;12(8):542–563.

- Mizokami T, Wu Li A, El-Kaissi S, Wall JR. Stress and thyroid autoimmunity. Thyroid. 2004 Dec;14(12):1047-55.

- Vita R, Lapa D, Trimarchi F, Benvenga S. Stress triggers the onset and the recurrences of hyperthyroidism in patients with Graves’ disease. Endocrine. 2015 Feb;48(1):254-63.

- Stewart T, Rochon J, Lenfestey R, et al. Correlation of stress with outcome of radioiodine therapy for Graves’ disease. Journal of Nuclear Medicine : Official Publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 1985 Jun;26(6):592-599.

- Yoshiuchi K, Kumano H, Nomura S, et al. Psychosocial factors influencing the short-term outcome of antithyroid drug therapy in Graves’ disease. Psychosom Med. 1998 Sep-Oct;60(5):592-6.

- Bassi V, Santinelli C, Iengo A, Romano C. Identification of a correlation between Helicobacter pylori infection and Graves’ disease. Helicobacter. 2010 Dec;15(6):558-62.

- Hou Y, Sun W, Zhang C, et al. Meta-analysis of the correlation between Helicobacter pylori infection and autoimmune thyroid diseases. Oncotarget. 2017;8(70):115691–115700.

- Janegova A, Janega P, Rychly B, et al. The role of Epstein-Barr virus infection in the development of autoimmune thyroid diseases. Endokrynol Pol. 2015;66(2):132-6.

- Dittfeld A, Gwizdek K, Michalski M, et al. A possible link between the Epstein-Barr virus infection and autoimmune thyroid disorders. Cent Eur J Immunol. 2016;41(3):297–301.

- Nagata K, Fukata S, Kanai K, et al. The influence of Epstein-Barr virus reactivation in patients with Graves’ disease. Viral Immunol. 2011 Apr;24(2):143-9.

- Kannangai R, Sachithanandham J, Kandathil AJ, et al. Immune responses to Epstein-Barr virus inindividuals with systemic and organ specific autoimmune disorders. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2010 Apr-Jun;28(2):120-3.

- Nagata K, Hara S, Nakayama Y, et al. Epstein-Barr virus lytic reactivation induces IgG4 production by host B lymphocytes in Graves’ disease patients and controls: a subset of Graves’ disease Is an IgG4-related disease-like condition. Viral Immunol. 2018;31(8):540–547.

- Yuan L, Tian Y, Zhanstudy. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129773. Published Jun, 19 2015.

- Bauer M, London ED, Silverman DH, et al. Thyroid, brain and mood modulation in affective disorder: insights from molecular research and functional brain imaging. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003 Nov;36 Suppl 3:S215-21.

- Hyperthyroidism. Penn State Hershey website. http://pennstatehershey.adam.com/content.aspx?productid=107&pid=33&gid=000088. Accessed June 25, 2020.

- Nordio M. A novel treatment for subclinical hyperthyroidism: a pilot study on the beneficial effects of l-carnitine and selenium. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21(9):2268-2273.

- Genere N, Stan MN. Current and Emerging Treatment Strategies for Graves’ Orbitopathy. Drugs. 2019;79(2):109-124. doi:10.1007/s40265-018-1045-9.

- Marinò M, Dottore GR, Leo M, Marcocci C. Mechanistic Pathways of Selenium in the Treatment of Graves’ Disease and Graves’ Orbitopathy. Horm Metab Res. 2018;50(12):887-893. doi:10.1055/a-0658-7889.

- Marcocci C, Kahaly GJ, Krassas GE, et al. Selenium and the course of mild Graves’ orbitopathy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(20):1920-1931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1012985.

- Heisel CJ, Riddering AL, Andrews CA, Kahana A. Serum Vitamin D Deficiency Is an Independent Risk Factor for Thyroid Eye Disease. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36(1):17-20. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001437.

- Sinclair C, Gilchrist JM, Hennessey JV, Kandula M. Muscle carnitine in hypo- and hyperthyroidism. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32(3):357-359. doi:10.1002/mus.20336.

- How Does L-Carnitine Help With Hyperthyroidism and Graves Disease? Natural Endocrine Solutions website. https://www.naturalendocrinesolutions.com/articles/how-does-l-carnitine-help-with-hyperthyroidism-and-graves-disease/. Accessed June 25, 2020.

- Benvenga S, Ruggeri RM, Russo A, Lapa D, Campenni A, Trimarchi F. Usefulness of L-carnitine, a naturally occurring peripheral antagonist of thyroid hormone action, in iatrogenic hyperthyroidism: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(8):3579-3594. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.8.7747.

- Yildirim S, Yildirim A, Dane S, Aliyev E, Yigitoglu R. Dose-dependent protective effect of L-carnitine on oxidative stress in the livers of hyperthyroid rats. Eurasian J Med. 2013;45(1):1-6. doi:10.5152/eajm.2013.01.

- Zielsdorf S. TheThyroid Secret. 2017.

- Osansky E. TheThyroid Secret. 2017.

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. We are a professional review site that receives compensation from the companies whose products we review. We test each product thoroughly and give high marks to only the very best. We are independently owned and the opinions expressed here are our own.

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. We are a professional review site that receives compensation from the companies whose products we review. We test each product thoroughly and give high marks to only the very best. We are independently owned and the opinions expressed here are our own.

Thank you for the great information that you posted about Graves disease. I have had Graves disease since I was 21 years old after my first child. I am now 68 years old. You gave me a lot of information that I can use and to talk with my Dr about. It has been awhile since I had a T3 and T4 done. I have a lot of diarrhea issues and I have a lot of stress. My husband is in a nursing home and I don’t think he will be coming out of there.

Judy, you are very welcome. I am so sorry to hear about your husband. <3 My heart goes out to you and him. I do hope you will keep me posted on your progress.

Dear Izabella Went

Thank you so much for the article on same root causes for Hashimotos and Graves.

I am a woman, 63 years of age were diagnosed with Graves in 2015 following a uterus cancer operation in 2014.

For one year I had medication Thycapzol – decided to try to find alternatives like diet or meditation. I am living in Denmark – and it is very very difficult to even discuss anything other than medication to fight Graves. The doctors will not even speak to me – just telling me that it is dangerous for me to go on without medication. They do not want to talk about the underlying causes. I am still here in 2020 – taking no medication but vitamins and minerals. I have just bought on your recommendation a Danish product called L-Carnitin including vitamin C and I am looking forward to testing it. The kindest regards Nanna Lützen. Facebook: Nanna Lützen

Nanna – thank you so much for sharing your journey with me. <3 I highly recommend that you work with a functional medicine clinician. It’s an entire medical specialty dedicated to finding and treating underlying causes and prevention of serious chronic diseases, rather than disease symptoms. I believe that everyone needs to find a practitioner that will let him/her be a part of the healthcare team. You want someone that can guide you, that will also listen to you and your concerns. You want someone that’s open to thinking outside of the box and who understands that you may not fit in with the standard of care. It's a good idea to ask some standard questions when contacting a new doctor for the first time. Something else to consider is you can work with a functional doctor remotely, via Skype. You could also contact your local pharmacist or compounding pharmacy, who may be able to point you to a local doctor who has a natural functional approach. But I encourage you to keep looking for the right one for you! Here are some resources you might find helpful.

CLINICIAN DATABASE

https://thyroidpharmacist.com/database-recommended-clinicians/

FIND A FUNCTIONAL MEDICINE CLINICIAN

https://ifm.org/find-a-practitioner/

Thank you Dr Izabella for such a compressive overview. I was diagnosed late 2019 and was put on bets blockers. I am thankful to have a endocrinologist and acupuncturist that focus in supplements and diet and are not trying to make me remove my thyroid. I’m still working to get off the blockers and methimazole. You had such great pieces of new information that will be helpful. I guess it’s going to be a lifelong journey but knowing people like you are out there willing to share and educate. God Bless You!

Tina – thank you so much for sharing your journey. <3 I'm so glad you found this article helpful. Please keep me posted on your progress.

I have gotten back a CT scan with iodine and I have gotten hyperthyroid, severe how long does this last if the iodine brought it on, and are you taking patient s

Sandy – thank you for reaching out. I’m so sorry! ❤️ Everyone is different. I do recommend that you discuss your concerns with your practitoner, listen to your body and monitor your thyroid labs. I do provide a limited number of consultations, however, at present time I am not accepting new clients. I have a 12 week online program called Hashimoto’s Self-Management Program, that covers all of the strategies that I go through with my one-on-one clients, in a self-paced format, so that participants have access to all of the things I’ve learned about Hashimoto’s without having to schedule costly consults with me or another practitioner. There are a few requirements that you should pay attention to before enrolling to this course, like reading my book. Here is the link to the program:

Hashimoto’s Self-Management Program

https://thyroidpharmacist.com/enroll-in-hashimotos-program/

If you would like to be notified of any future consulting opportunities and educational events, you can sign up for my waiting list: https://thyroidpharmacist.com/dr-izabella-wentzs-waiting-list/

Could you please give the reference or link for the “2013 Chinese study (that) found a rate of H. pylori infection in 66 percent of people with Graves’ disease and 37.7 percent of people with Hashimoto’s.” which you mention? I cannot see which one it is in the references you give? Thank you.

Kate – thank you for following! ❤️ Please email my team at info@thyroidpharmacist.com and they will be happy to help you!

Hi Izabella, could you please expand on the use of lemon balm in people with Hashimoto’s? I’ve found a very good supplement which has lemon balm in it (200mg per 7g sachet), but I’ve read elsewhere that lemon balm should be avoided completely by people with Hashimoto’s… Is this really so? Thanks!

Kelly – thank you for reaching out. Everyone is different and will respond differently to supplments. I recommend discussing with your practitioner to help you determine if it is an option for you.

Hello, My teenage daughter had recent blood work done and TSH was extremely low with elevated T3/T4. This is new. She has been taking a herbal allergy supplement with various herbal extracts for a few weeks, and she also started drinking soy milk this week. We use iodized salt. Could the herbal supplement or the soy milk affect the thyroid? Thank you in advance

Joanne – thank you for reaching out. Everyone is different and she may be sensitive to those. Soy is a known endocrine disruptor, and has been linked to altered hormone function and increased thyroid antibodies. It is a xenoestrogen chemical that mimics the effect of estrogen. As estrogen increases our need for thyroid hormone, it’s possible that exposure to these chemicals may increase TSH, resulting in a triggering of the autoimmune process. Here are some articles that you might find helpful:

HOW AVOIDING SOY CAN BENEFIT HASHIMOTO’S

https://thyroidpharmacist.com/articles/soy-and-hashimotos/

FOOD SENSITIVITIES AND HASHIMOTO’S

https://thyroidpharmacist.com/articles/food-sensitivities-and-hashimotos/

WHERE DO I START WITH HASHIMOTO’S?

https://thyroidpharmacist.com/articles/where-do-i-start-with-hashimotos/