Long before I was diagnosed with Hashimoto’s, I was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and this specific diagnosis (or perhaps the symptoms associated with it) was the most important clue to the root cause of my Hashimoto’s and numerous symptoms.

My story with IBS starts with ramen noodles covered in soy sauce. I was a graduate student, and this was my go-to meal to fuel my late-night study sessions.

This particular night, I went to bed around 2 a.m., feeling very confident about my ability to “ace” the exam I had been studying for all day and evening.

But alas, my plans were foiled, as I was awakened around 4 a.m. with the worst kind of stomach cramping. I crawled out of bed and nearly doubled over in pain before I made my way to the bathroom and experienced an excruciating bout of explosive diarrhea.

It was the first of many that late night, and I was still running back and forth between the bathroom and my bed when it came time to drive to my exam. (I apologize if this is TMI [too much information], but we are talking about IBS here. ;-))

I thought my digestive distress would be a one-time thing, perhaps due to food poisoning, but unfortunately, the symptoms kept coming back, and I started regularly struggling with digestive issues.

Soon thereafter, I was diagnosed with IBS.

I was given a prescription for Levsin, an antispasmodic and anticholinergic drug that works by blocking the effects of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine to slow down digestive secretions and gut motility, thereby reducing explosive stools. I was hopeful it would solve my embarrassing symptoms… but unfortunately, I soon realized this old school drug had many side effects.

While I no longer experienced diarrhea with this medication, I did start experiencing constipation. I also experienced dry eyes, dry mouth, and dizziness that impacted my everyday life.

At the time, I didn’t really know about the root cause approach to healing, so I just adjusted my life to my symptoms – I never left home without diarrhea medicine and an extra pair of pants.

Eventually, I was diagnosed with Hashimoto’s, and I later learned that many people with Hashimoto’s (and other autoimmune conditions) receive an IBS diagnosis 5 to 15 years before their autoimmune diagnosis. This matches perfectly with my own health timeline.

When I dug deeper into my health, I came to realize that the key to reversing Hashimoto’s was in solving my digestive issues, and this is actually a big part of my approach to Hashimoto’s.

This is because untreated digestive issues leave a person with lingering intestinal permeability – a precursor to autoimmunity. Some people talk about eliminating foods or drinking bone broth to heal the gut, but this approach often falls short. This is because digestive symptoms have numerous potential root causes – and they CAN be addressed. I’ve learned about the many triggers and causes of digestive issues in the last 10+ years, and I’m so excited to finally share them with the world.

Even if you’ve been told that your digestive symptoms are “just IBS” and you can’t really “do anything about it,” I want to share that your symptoms may be caused by a medically identifiable, treatable, and often testable condition, such as celiac disease, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), or a protozoal infection, just to name a few. When these root causes are addressed, we see a real shift in symptoms and long-lasting healing.

In this article, you will discover:

- What is considered IBS

- Risk factors for IBS

- The connection between IBS and the thyroid

- The conventional approach to IBS (and why it often doesn’t work)

- The root cause approach to IBS

What is IBS vs. Healthy Digestion?

Many of us have learned to live with our digestive troubles for so long that we’ve come to think of them as just the way things are. We may not even know what healthy digestion is, because what we are used to can become our new normal!

Here are a few signs of healthy digestion:

- Most foods can be digested without causing bloating, cramps, fatigue, or pain (I know this was shocking to me personally!).

- Regular and frequent bowel movements that pass approximately one minute after sitting on the toilet, without pain or strain, and without needing to use your fingers to press on your anus to poop.

- Regularity is defined as bowel movements that come at a predictable time, often in the morning, 20 to 40 minutes after eating, or 20 to 40 minutes after other daytime meals.

- Frequency does vary from person to person, where some pass a stool as often as one to three times per day, and others might do so every other day. Going less frequently than three to four times per week may be a sign of constipation.

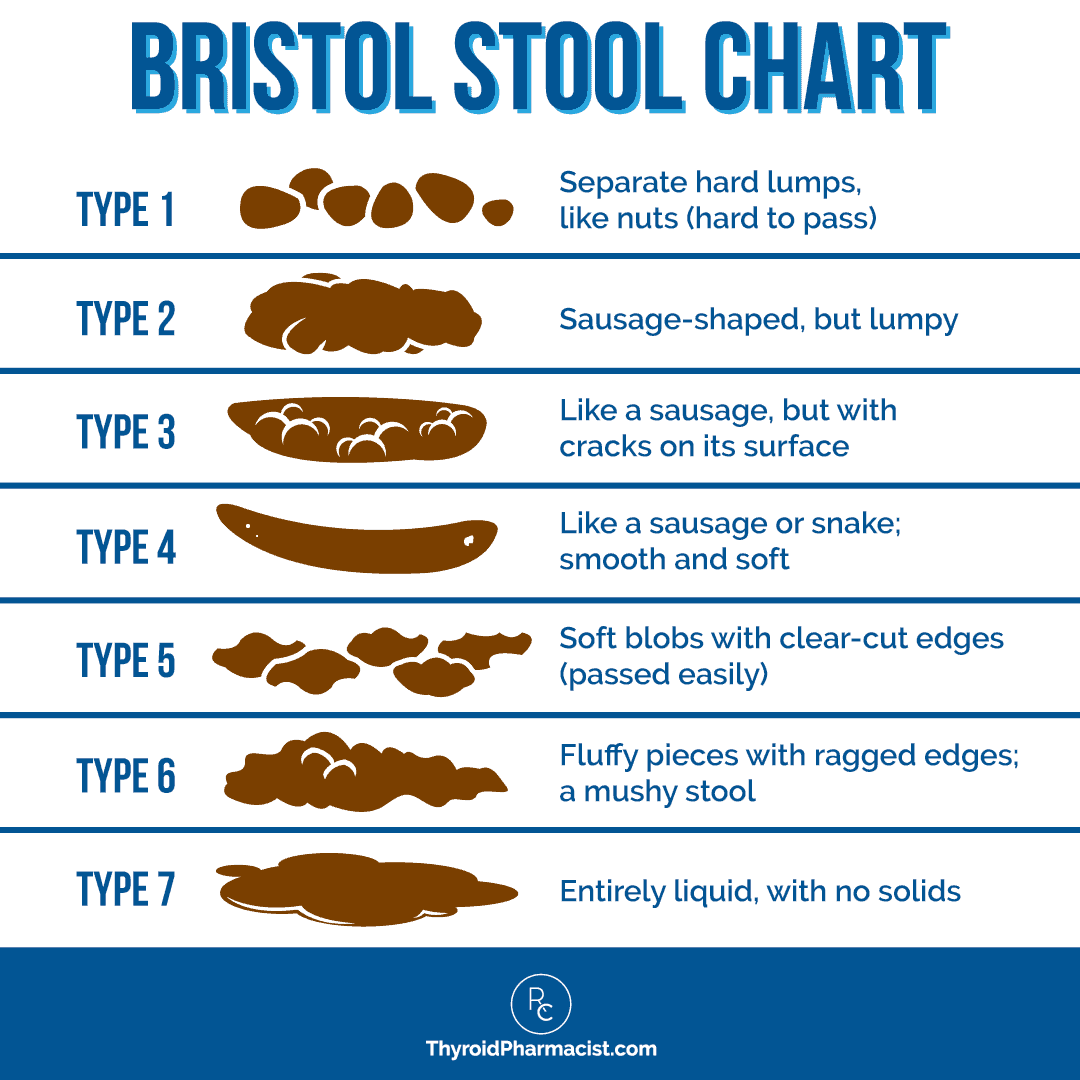

- Soft, well-formed, brown stool ranging between type 3, “a sausage shape with cracks in the surface,” and type 4, “like a smooth, soft sausage or snake,” on the Bristol Stool Form Scale – or as I like to call it, “The Official Poop Chart” (see below).

Now that we have covered healthy digestion, let’s talk about the common, but not normal, opposite end of the spectrum: irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

In the past, doctors have referred to irritable bowel syndrome as nervous colon, spastic bowel, colitis, and mucous colitis, and P.W. Brown eventually coined the term irritable bowel syndrome in 1948. [1] The term was used to describe symptoms of constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal pain when no infectious cause was identified.

IBS accounts for 12 percent of visits to primary care physicians and is one of the most common functional digestive disorders, a group of disorders in which the gastrointestinal tract isn’t working quite right, but there isn’t a structural or biochemical abnormality that can be easily measured or seen.

People with IBS can have a variety of symptoms, including: [2]

- Abdominal pain, cramping

- Changes in bowel frequency

- Change in bowel movement appearance (pellet-shaped, watery)

- Bloating or swelling

- Relief of pain with bowel movement

- Sensation of incomplete passing of stools

- Mucus in stool

- Difficulty with bowel movements, such as straining

- Other gastrointestinal symptoms such as excess gas, acid reflux, heartburn, fullness after eating, belching, and nausea

- Psychological symptoms such as depression and anxiety (which may be present in up to one third of people, with some studies indicating that as many as 60 percent of people with IBS have anxiety)

- Symptomatic flares or periods of remission

- Other common co-occurring symptoms such as fatigue, frequent urination, back pain, headache, and bad breath or an unpleasant taste in the mouth

Testing and Diagnosis

Up until recently, there has not been a definitive test to rule out or confirm IBS, so diagnosis is based on medical history (including family history), self-reported clinical symptoms, and evaluation of current medications. One report found that it takes about four years on average for people to be given an IBS diagnosis. [3]

Until the 1970s, IBS was a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning it was given after extensive lab testing and procedures, even surgery, were done to rule out other potentially diagnosable diseases. If everything came back “normal,” doctors would dub the condition “IBS.”

Currently, the Rome IV criteria is the most commonly used diagnostic criteria. It states that the patient must have recurrent abdominal pain for at least three months (and on average at least one day per week), with symptom onset at least six months prior to diagnosis. Additionally, they must meet two or more of the following criteria:

- Pain specifically related to defecation. Pain is the most common symptom of IBS and could involve the presence of abdominal pain (often described as severe muscle tension and cramping) associated with straining and constipation, and/or the urgency to pass loose stool and diarrhea. Pain typically decreases after a bowel movement.

- Changes in frequency of stool (how often, urgency). People can have a combination of normal bowel habits (regular and easy to pass) that alternate with frequent loose stools, including a heightened sense of urgency to defecate, and/or constipation that can last for days or longer. Defecating may include a feeling of incomplete relief after defecation.

- Changes in the appearance of stool (such as diarrhea and/or constipation, and the presence of mucus in the stool). Stool may be hard, lumpy, and difficult to pass, characteristic of constipation, or watery, mushy, and shapeless, characteristic of diarrhea. The presence of noticeable amounts of mucus, a clear or whitish jellylike substance that helps lubricate the colon, has been reported in 50 percent of people with IBS. This may be due to dehydration or constipation, but has also been observed as a characteristic in the diarrhea-predominant type of IBS.

Unfortunately, IBS is still mostly diagnosed based on symptoms, and once a doctor “labels” an individual’s set of symptoms as IBS, there is rarely any further investigation into what might really be going on. And as conventional treatment isn’t meant to “cure” IBS, just manage symptoms, that label basically becomes a life sentence.

There are some newer blood tests that may help doctors make an IBS diagnosis, such as the IBSchek and IBS-Smart tests, which measure antibodies associated with the development of IBS after a gastrointestinal infection. But in general, current medical guidelines do not recommend testing for people who meet diagnostic criteria.

I personally believe that people struggling with IBS symptoms deserve a thorough investigation, which is what inspired my upcoming book, IBS: Finding and Treating the Root Cause of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. It releases on March 17th and is currently available for preorder. As a thank you for preordering, I will send you my Gut Symptoms Solution Guide, which provides a broad-spectrum protocol to support healthy intestinal permeability (leaky gut), which plays a key role in both IBS and autoimmune disease. To get your free gift (plus a few other preorder goodies!), simply preorder IBS: Finding and Treating the Root Cause of Irritable Bowel Syndrome, then visit this page and enter your order number and email, and I will send the free gifts straight to your inbox, so you can start healing right away.

Types of IBS

With such a range of associated symptoms, it’s not surprising that IBS can present differently in different people. While one person with IBS may be regularly running to the bathroom with urgent diarrhea (like I was), another person may struggle to pass a painfully hard stool. To reflect these differences, four distinct diagnostic types of IBS have been created:

- IBS with constipation (IBS-C): More than 25 percent of abnormal bowel movements consist of lumpy and hard poop. Constipation happens when food moves too slowly through the digestive tract and the colon or large intestine absorbs too much water from the partially digested food, making it dry and difficult to pass. Studies suggest that women are significantly more likely to develop IBS-C than men. [4]

- IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D): More than 25 percent of abnormal bowel movements consist of watery and loose poop. In this case, waste is passing through the digestive system too quickly for the colon to absorb enough water, so that the stool is very runny. This is the most common type of IBS, reported by about 40 percent of people. [5]

- IBS with mixed bowel habits (IBS-M): As the name implies, in this type of IBS, the person will have a mixture of constipation and diarrhea, which can alternate as quickly as a few hours, while other people will alternate on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis. [6]

- IBS unclassified (IBS-U): Most of your poop is normal, but you have recurring stomach pain and other IBS symptoms.

Different people can experience different combinations of symptoms (which can also change over time, even changing IBS type).

Is it IBS or Something Else?

I know too many people who have been told they had “irritable bowel syndrome,” when indeed they had another condition, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or celiac disease. Statistics say that a whopping 10 percent of people with IBD may be misdiagnosed with IBS, and in one study, 25 percent of people labeled as “IBS” actually had celiac disease! [7]

Several other conditions share the same symptoms as IBS, with which someone may be diagnosed. These include a wide spectrum of conditions such as acute cholecystitis and biliary colic, bacterial or viral gastroenteritis, SIBO, celiac disease, pancreatitis, microscopic colitis, lactose intolerance, ulcerative colitis, and even cancer.

I would love to say that every health care practitioner is aware of “red flag” symptoms that warrant deeper investigation, but unfortunately, that is not often the case in the real world.

Whether a practitioner does further evaluation or testing to exclude any of these other “possibilities” (referred to as differential diagnosis) depends on how well a patient reports their symptoms and health history, as well as the knowledge and determination of the practitioner to peel back the onion and figure out what’s really going on!

As a young pharmacy student, I really thought that all doctors had a certain level of competence, but after a few months of working at a pharmacy in East Los Angeles, I realized that was sadly not the case in the real world.

Risk Factors for IBS

While people of all ages and backgrounds have IBS, there are certain factors shown to increase the likelihood of developing it. These include:

- Having a family history of IBS or other gastrointestinal disorders: There is thought to be a genetic component, as well as the possible influence of a family’s shared environment (including diet).

- Female gender or those using female hormones: In the U.S., IBS symptoms are 1.5 to 2 times more prevalent among women than men. [8] While specific studies relating to estrogen levels and their association with IBS have been inconclusive, some studies have found that women with IBS have an increased perception of pain linked to the decrease in levels of ovarian hormones during their period. [9] Postmenopausal women who use hormone replacement therapy (HRT) seem to be more likely to develop IBS than women who do not use HRT, supporting a connection between female sex hormones and IBS symptoms. [10]

- Under age 50: IBS is usually diagnosed in the late teens to early 40s.

- Mental health issues or a history of physical or sexual abuse: Having depression, somatization disorder, anxiety, panic disorder, and/or social phobia have been identified in more than 50 percent of patients with IBS. IBS is more common in patients who have experienced physical or sexual abuse, who abuse alcohol, or who have experienced stressful life events, such as a death in the family or divorce, before they developed IBS symptoms. [11]

- Recent and severe digestive tract infection: Risk of IBS was found to be four times higher in individuals who had infectious enteritis (a.k.a. “food poisoning”) prior to symptom onset of IBS. Research has found that approximately one in 10 patients with IBS believes that their IBS began with an infectious illness. [12]

I will say that conventional medicine experts often assume that pathogens have been “cleared” by the body when they are, in fact, happily reproducing within our gut! Lingering infections are a big cause of IBS in my experience, thanks to having access to advanced testing for infections, but sadly, most methods used by conventional practitioners fail to detect these infections and wrongly assume that they have passed.

The Thyroid and IBS Connection

Many people with thyroid issues have IBS, and vice versa. It’s my educated guess that IBS-D often develops first, then this leads to malabsorption of vital nutrients required for thyroid function, resulting in hypothyroidism, which can eventually lead to constipation.

Thyroid hormones regulate every metabolic process in the body, so any imbalance can significantly disrupt digestive function. [13]

In hypothyroidism, low levels of thyroid hormones can slow down all bodily processes, including digestion. Inadequate amounts of digestive enzymes and bile are produced to support the proper breakdown and absorption of food, contributing to poor digestion, food sensitivities, gut dysbiosis, and intestinal permeability (adding fire to the immune system attack!).

Interestingly, thyroid disorders and IBS have many overlapping features and root causes:

Disrupted Motility

Transit time (the rate at which food moves through the digestive system) is also regulated by thyroid hormones and will slow down when thyroid hormones are low, which can contribute to constipation (which is the most common GI symptom in hypothyroidism and a top complaint of my clients with Hashimoto’s).

Imbalance of Gut Bacteria

Slowed motility can then lead to imbalances in the microbiome, also known as dysbiosis. Studies have shown that those with hypothyroidism have an altered composition of gut bacteria with reduced populations of the beneficial short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria, and higher levels of inflammation-driving lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-producing bacteria. [14] A deficiency of beneficial bacteria with excess pathogenic bacteria is also a key feature in those with IBS. [15]

Intestinal Permeability

Intestinal permeability (leaky gut) is one of the three factors that must be present for autoimmune disease to develop, in addition to a genetic predisposition and an environmental trigger (such as an infection or major stressor). [16] Studies have found that people with IBS are likely to have increased intestinal permeability, though not everyone with IBS will have it. Certain types of IBS are more prone to it, with one study finding that barrier function was most likely to be compromised in people with IBS-D (37 to 62 percent), followed by post-infectious IBS (17 to 50 percent), and IBS-C (4 to 25 percent). [17]

Infections

Chronic infections caused by certain bacteria, protozoa/parasites, and fungi/yeast are common in those with Hashimoto’s (some studies indicate SIBO may be present in as many as 50 percent of people with hypothyroidism), and they can lead to diarrhea. [18] For some people with IBS, infections can be a trigger for their symptoms. Viruses associated with gastroenteritis (also known as the stomach flu) have been found to be a strong risk factor for developing IBS (called post-infectious IBS or PI-IBS), with exposed individuals 4.5 times more likely to develop PI-IBS within 12 months after infection. [19] For some, eliminating a SIBO infection can resolve their IBS.

Stress

Another common thread between Hashimoto’s and IBS is stress! Periods of stress often precede the onset of autoimmune conditions – in fact, in my survey of over 2,000 readers with Hashimoto’s, 69 percent reported a lot of stress in their lives before they began to feel unwell. [20] Whether or not you have IBS, many of us know that stress can impact our digestion in all sorts of ways. The main effects of stress on the gut include alterations in gut motility, increased sensitivity in the gut, changes in gut secretions (such as stomach acid and bile, which can impact digestion and nutrient absorption), increased intestinal permeability, a reduced ability for the gut to replenish its mucosal layer, reduced mucosal blood flow, and negative alterations of intestinal microbiota. [21] Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are associated with an increased risk of both IBS and autoimmune disease, and research has found that people with IBS are more likely to have experienced trauma of any kind than people without IBS. [22]

Symptoms of hypothyroidism and IBS resemble each other so closely that many people with thyroid dysfunction are diagnosed with IBS prior to getting their thyroid adequately tested. An interesting report from Nepal found that 18.5 percent of people who have IBS actually have thyroid dysfunction, most of them subclinical hypothyroidism (the early stages). [23]

The Conventional Approach to IBS

Much like with Hashimoto’s, the conventional medicine approach to IBS focuses primarily on lessening and managing symptoms, rather than searching for a root cause.

Depending on the type of IBS someone has and the symptoms they are experiencing, they may be told to try an OTC or prescription medication intended to treat their symptoms. Some doctors may also recommend diet and lifestyle changes, and stress management strategies, but those are, of course, few and far between.

It’s no surprise that without tailoring treatments to a cause, symptom relief following conventional treatment for IBS is incredibly poor, with one study finding that less than 25 percent of people gained complete relief from any given symptom. [24] Current conventional management therapies for patients with IBS result in up to 50 percent of patients remaining significantly symptomatic as much as six years after diagnosis. [25]

The good news is, whether you’ve just been diagnosed with IBS or have been struggling with symptoms for years, finding and addressing your unique root cause(s) can help significantly!

The Root Cause Approach to IBS

In functional medicine, we focus on the underlying causes for individual IBS symptoms, and we recognize this may require peeling back multiple layers of root causes as well. In my clinical experience, about 80 percent of people with “IBS” will find a resolution to their symptoms by following the root cause approach.

When we can identify specific root causes and resolve them, we can free ourselves from IBS-like symptoms and the autoimmune cycle.

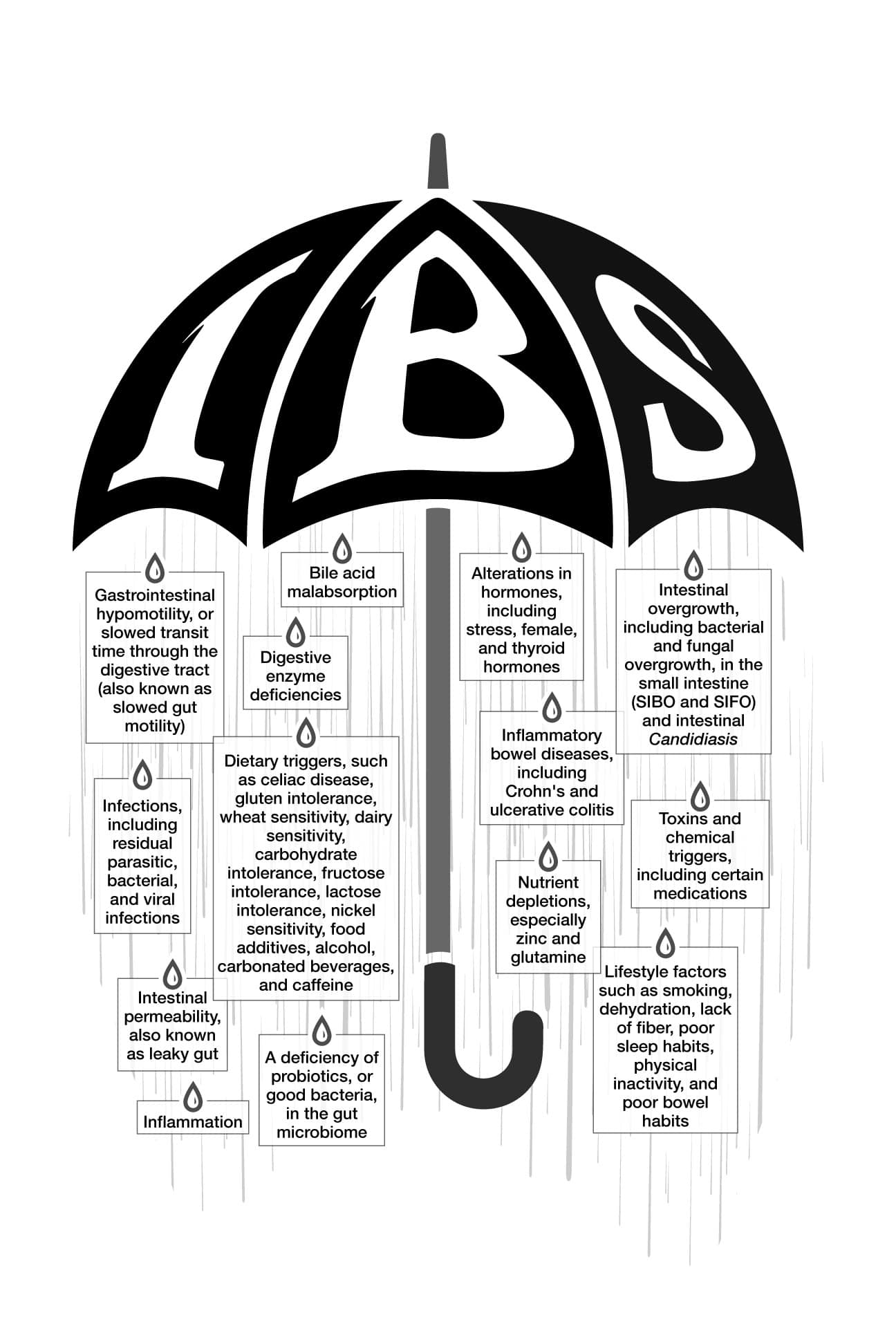

Let’s look at some of the most common root causes for IBS symptoms that I have seen in clinical practice and in the research (that are largely overlooked by the majority of conventional practitioners). Please keep in mind that while these are the most common root causes and the ones I most frequently see in my clients, these aren’t the only potential root causes:

- Dietary triggers: My work with Hashimoto’s really opened my eyes to the impact of dietary triggers on overall health and disease development, as well as the profound effect these can have on digestive symptoms. Studies have found that 50 to 80 percent of IBS patients identify a particular food as a possible trigger for their IBS symptoms, and up to 25 percent of people with an IBS diagnosis may actually have celiac disease. [26]

- Digestive enzyme deficiencies: IBS-like symptoms can occur due to a person’s inability to digest various food components, including protein, fat, and starches. This can often be corrected by taking the right digestive enzyme in the correct dose. Some enzyme deficiencies can be uncovered by comprehensive testing, while others are best trialed if symptoms suggest a deficiency. Some people may benefit from broad-spectrum enzymes, while others may benefit from very targeted enzymes.

- Bile acid malabsorption: Bile helps to break down fat in the small intestine. If it’s inadequately reabsorbed after doing its work, bile can make its way into the colon and trigger diarrhea. Treating bile acid malabsorption may help clear up diarrhea in 30 percent of cases of IBS-D. [27]

- Nutrient depletions: Deficiencies in a few key nutrients related to gut health, such as glutamine, vitamin D, thiamine, carnitine, vitamin A, zinc, and others, may contribute to IBS symptoms.

- Deficiency of beneficial bacteria with excess pathogenic bacteria: A 2020 meta-analysis found that people with IBS often have a microbiome pattern characterized by not enough “good” bacteria and too much “bad” bacteria and/or yeast in the microbiome. [28] This is similar to findings in those with Hashimoto’s.

- Intestinal permeability: Studies have found that people with IBS are likely to have increased intestinal permeability, though not everyone with IBS will have it. [29] As we know, those with Hashimoto’s nearly always have some level of intestinal permeability.

- Intestinal overgrowth of bacteria or yeast: Research has found that one-third of IBS patients tested positive for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, or SIBO. An overgrowth of Candida in the small intestine has been found in about 25 percent of people with previously unexplained GI symptoms, like those associated with IBS.

- Gastrointestinal hypomotility (also known as slowed gut motility): Abnormal gut motility is associated with low muscle tone in the gut, vagus nerve issues, mitochondrial dysfunction, hypothyroidism, certain medications, and other metabolic conditions such as diabetes and obesity. [30] Slower gut motility typically leads to constipation, but it can also cause diarrhea, along with a host of other IBS-like symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort, bloating, flatulence, and nausea.

- Alterations in stress hormones: While most people with common sense can connect stress to IBS, researchers have explained how this happens. A 2008 study highlighted that stress reduces beneficial bacteria in the gut and allows pathogenic bacteria to proliferate. [31]

- Alterations in female hormones: Estrogen and its receptors play an important role in the development of many GI disorders, including IBS. [32] Many women (both with and without IBS) experience an increase in GI symptoms before and during their menstrual cycles, and in early menopause.

- Thyroid imbalances and autoimmunity: A dysregulation of thyroid hormones in itself can lead to digestive distress and is a very common finding in IBS. Hypothyroidism causes a slowing down in the digestive process, while hyperthyroidism (having an overactive thyroid gland) can lead to diarrhea. With Hashimoto’s, there is an autoimmune attack against the thyroid, resulting in fluctuating thyroid hormone levels. Some people may initially experience a surge in thyroid hormone levels during the early stages of the autoimmune attack, followed by low levels of thyroid hormone, resulting in fluctuating GI symptoms.

- Infections: Chronic infections are an overlooked source of leaky gut and IBS-like symptoms, yet identifying and treating them correctly can have a tremendous impact on how you feel. I’ve spoken at length about Blastocystis hominis being one of the most prevalent triggering infections in Hashimoto’s. It also happens to be a known trigger for IBS and chronic hives, so if you have all three, I am willing to bet some hard cash that you probably have this infection and that treating it will result in a remission of all three conditions. But there are many other infections, and testing is key to finding out which infection you might have.

- Inflammation: Although the extent of the inflammation is not as severe as in cases of IBD, people with IBS have been found to have markers indicating higher levels of chronic, low-grade inflammation compared to healthy controls. [33]

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease: IBS and IBD share several of the same symptoms, and there are many instances when IBD is missed. According to some studies, as many as 10 percent of people with IBD may be misdiagnosed with IBS, and IBD patients are three times more likely to have a previous diagnosis of IBS. [34] While there are heavy-duty drugs for IBD, there are also lifestyle changes that are (in my humble opinion) much safer and often more effective.

- Toxins and chemical triggers: We are exposed to countless toxic substances on a daily basis through the foods we eat, the air we breathe, and the products we apply to our skin. Research shows that these toxins can disrupt the microbiome and cause widespread inflammation, including in the gut. [35]

While it may take some time and experimentation to get to the root of your digestive issues, it is possible. I have seen this approach help so many people take back their health and transform their lives. I wholeheartedly believe it can do the same for you!

This is exactly what inspired my upcoming book, IBS: Finding and Treating the Root Cause of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Inside, you’ll discover much deeper dives on all the potential root causes I’ve listed in this article, plus you’ll learn about how digestive symptoms often show up 5 to 15 years before an autoimmune diagnosis, how to utilize targeted nutrition strategies, how to restore microbial balance, and how to restore intestinal permeability.

Whether you’ve been struggling with Hashimoto’s for many years or you were just diagnosed (and even perhaps received an IBS label), I hope my comprehensive guide to figuring out the root causes of gut issues will help you heal!

The book officially comes out on March 17th, but I don’t want you to wait to start healing, so I am offering you an exclusive bonus when you preorder now – my Gut Symptom Solutions Guide. This eBook walks you through a broad-spectrum protocol to support healthy intestinal permeability (leaky gut) , which plays a key role in both IBS and autoimmune disease. Plus, you’ll receive an exclusive preview chapter on inflammatory bowel disease and my Figuring Out Food Sensitivities Guide. Find more information and submit your proof of purchase to get these preorder bonuses here.

This book has been decades in the making, and I’m so excited to share with you all I’ve learned.

Takeaway

There is a complex, bidirectional relationship between the thyroid and IBS, and in many cases, these conditions do not occur in isolation. They may share underlying root causes such as chronic inflammation, gut dysbiosis, nutrient deficiencies, infections, or stress.

If you’re feeling hopeless about ongoing digestive symptoms or frustrated that conventional treatments haven’t provided you with lasting relief, it may be time to dig deeper.

Identifying and addressing your unique root cause can help you achieve more meaningful and sustainable healing, rather than simply managing symptoms.

If this sounds like you, I highly suggest preordering IBS: Finding and Treating the Root Cause of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Whether you’re newly diagnosed or have been struggling for years, this book will walk you through the exact steps to identify what’s driving your symptoms and how to address those root causes with confidence. You’ll learn how to work smarter, not harder, using the latest research and real-world strategies that actually make a difference.

Have you ever been diagnosed with IBS? Were digestive symptoms part of your Hashimoto’s experience? I’d love to hear your story in the comments!

P.S. You can download a free Thyroid Diet Guide, 10 thyroid-friendly recipes, and the Nutrient Depletions and Digestion chapter of my first book for free by signing up for my newsletter. You will also receive occasional updates about new research, resources, giveaways, and helpful information.

For future updates, make sure to follow me on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Pinterest!

References

[1] National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Definition & Facts for Irritable Bowel Syndrome. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Published November 2017. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/irritable-bowel-syndrome/definition-facts

[2] Saha L. Irritable bowel syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and evidence-based medicine. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(22):6759-6773. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6759; Palsson O, Whitehead W. IBS – beyond the Bowel: The Meaning of Co-Existing Medical Problems. UNC Center for Functional GI & Motility Disorders Accessed December 10, 2025. https://www.med.unc.edu/ibs/wp-content/uploads/sites/450/2017/10/IBS-Beyond-the-Bowel.pdf

[3] Black CJ, Ford AC. Global burden of irritable bowel syndrome: trends, predictions and risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(8):473-486. doi:10.1038/s41575-020-0286-8

[4] Kim YS, Kim N. Sex-Gender Differences in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24(4):544-558. doi:10.5056/jnm18082

[5] Farmer AD, Wood E, Ruffle JK. An approach to the care of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. CMAJ. 2020;192(11):E275-E282. doi:10.1503/cmaj.190716

[6] Palsson OS, Baggish JS, Turner MJ, Whitehead WE. IBS patients show frequent fluctuations between loose/watery and hard/lumpy stools: implications for treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(2):286-295. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.358

[7] Card TR, Siffledeen J, Fleming KM. Are IBD patients more likely to have a prior diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome? Report of a case-control study in the General Practice Research Database. United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2(6):505-512. doi:10.1177/2050640614554217

[8] Nathani RR, Sodhani S, Vadakekut ES. Irritable Bowel Syndrome. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; September 15, 2025.

[9] So SY, Savidge TC. Sex-Bias in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Linking Steroids to the Gut-Brain Axis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:684096. Published 2021 May 19. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.684096

[10] Bharadwaj S, Barber MD, Graff LA, Shen B. Symptomatology of irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease during the menstrual cycle. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2015;3(3):185-193. doi:10.1093/gastro/gov010

[11] Holten KB, Wetherington A, Bankston L. Diagnosing the patient with abdominal pain and altered bowel habits: is it irritable bowel syndrome?. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(10):2157-2162.

[12] Klem F, Wadhwa A, Prokop LJ, et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes of Irritable Bowel Syndrome After Infectious Enteritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(5):1042-1054.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.039; Saha L. Irritable bowel syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and evidence-based medicine. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(22):6759-6773. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6759

[13] Daher R, Yazbeck T, Jaoude JB, Abboud B. Consequences of dysthyroidism on the digestive tract and viscera. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(23):2834-2838. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.2834

[14] Fasano A. Leaky gut and autoimmune diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;42(1):71-78. doi:10.1007/s12016-011-8291-x

[15] Menees S, Chey W. The gut microbiome and irritable bowel syndrome. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1029. Published 2018 Jul 9. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14592.1; Shan Y, Lee M, Chang EB. The Gut Microbiome and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Annu Rev Med. 2022;73:455-468. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-042320-021020

[16] Fasano A. Leaky gut and autoimmune diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;42(1):71-78. doi:10.1007/s12016-011-8291-x

[17] Hanning N, Edwinson AL, Ceuleers H, et al. Intestinal barrier dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:1756284821993586. Published 2021 Feb 24. doi:10.1177/1756284821993586

[18] Patil AD. Link between hypothyroidism and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18(3):307-309. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.131155

[19] Berumen A, Edwinson AL, Grover M. Post-infection Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2021;50(2):445-461. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2021.02.007

[20] Stojanovich L, Marisavljevich D. Stress as a trigger of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7(3):209-213. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2007.11.007

[21] Konturek PC, Brzozowski T, Konturek SJ. Stress and the gut: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, diagnostic approach and treatment options. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62(6):591-599.

[22] Park SH, Videlock EJ, Shih W, Presson AP, Mayer EA, Chang L. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with irritable bowel syndrome and gastrointestinal symptom severity. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(8):1252-1260. doi:10.1111/nmo.12826; Köhler-Forsberg O, Ge F, Aspelund T, et al. Adverse childhood experiences, mental distress, and autoimmune disease in adult women: findings from two large cohort studies. Psychol Med. 2025;55:e36. Published 2025 Feb 11. doi:10.1017/S0033291724003544

[23] Khadka M, Kafle B, Khadga PK, Sharma S. Prevalence of Thyroid Dysfunction in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. ResearchGate. January 2018. Accessed December 17, 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322946988_Prevalence_of_Thyroid_Dysfunction_in_Irritable_Bowel_Syndrome.

[24] Brown B. Does Irritable Bowel Syndrome Exist? Identifiable and Treatable Causes of Associated Symptoms Suggest It May Not. ResearchGate. July 2019. Accessed December 17, 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334545135_Does_Irritable_Bowel_Syndrome_Exist_Identifiable_and_Treatable_Causes_of_Associated_Symptoms_Suggest_It_May_Not.

[25] Poon D, Law GR, Major G, Andreyev HJN. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of non-malignant, organic gastrointestinal disorders misdiagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1949. Published 2022 Feb 4. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05933-1

[26] Borghini R, Donato G, Alvaro D, Picarelli A. New insights in IBS-like disorders: Pandora’s box has been opened; a review. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2017;10(2):79-89.; Mansueto P, D’Alcamo A, Seidita A, Carroccio A. Food allergy in irritable bowel syndrome: The case of non-celiac wheat sensitivity. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(23):7089-7109. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i23.7089; Domżał-Magrowska D, Kowalski MK, Szcześniak P, Bulska M, Orszulak-Michalak D, Małecka-Panas E. The prevalence of celiac disease in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and its subtypes. Prz Gastroenterol. 2016;11(4):276-281. doi:10.5114/pg.2016.57941

[27] Farrugia A, Arasaradnam R. Bile acid diarrhoea: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020;12(6):500-507. Published 2020 Sep 22. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2020-101436

[28] Wang L, Alammar N, Singh R, et al. Gut Microbial Dysbiosis in the Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(4):565-586. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2019.05.015

[29] Camilleri M, Gorman H. Intestinal permeability and irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(7):545-552. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00925.x

[30] Yaylali O, Kirac S, Yilmaz M, et al. Does hypothyroidism affect gastrointestinal motility?. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2009;2009:529802. doi:10.1155/2009/529802; Abrahamsson H. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Intern Med. 1995;237(4):403-409. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.1995.tb01194.x; Miron I, Dumitrascu DL. GASTROINTESTINAL MOTILITY DISORDERS IN OBESITY. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar). 2019;15(4):497-504. doi:10.4183/aeb.2019.497

[31] Lutgendorff F, Akkermans LM, Söderholm JD. The role of microbiota and probiotics in stress-induced gastro-intestinal damage. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8(4):282-298. doi:10.2174/156652408784533779

[32] Chen C, Gong X, Yang X, et al. The roles of estrogen and estrogen receptors in gastrointestinal disease. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(6):5673-5680. doi:10.3892/ol.2019.10983

[33] Ng QX, Soh AYS, Loke W, Lim DY, Yeo WS. The role of inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). J Inflamm Res. 2018;11:345-349. Published 2018 Sep 21. doi:10.2147/JIR.S174982

[34] Card TR, Siffledeen J, Fleming KM. Are IBD patients more likely to have a prior diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome? Report of a case-control study in the General Practice Research Database. United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2(6):505-512. doi:10.1177/2050640614554217

[35] Kish L, Hotte N, Kaplan GG, et al. Environmental particulate matter induces murine intestinal inflammatory responses and alters the gut microbiome. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62220. Published 2013 Apr 24. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062220; Choi JJ, Eum SY, Rampersaud E, Daunert S, Abreu MT, Toborek M. Exercise attenuates PCB-induced changes in the mouse gut microbiome. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(6):725-730. doi:10.1289/ehp.1306534

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. We are a professional review site that receives compensation from the companies whose products we review. We test each product thoroughly and give high marks to only the very best. We are independently owned and the opinions expressed here are our own.

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. We are a professional review site that receives compensation from the companies whose products we review. We test each product thoroughly and give high marks to only the very best. We are independently owned and the opinions expressed here are our own.

I currently own a copy of Hoshimotos Protocol and I have already made the root cause smoothie, Chicken Tandoori, and have recently purchased black Seed oil. These changes have helped already although still struggling with major constipation. I pray by me keeping on reading that I am able to help this issue. Thank you so much for your knowledge and support! 😊

Taylor, That’s wonderful to hear, I’m so glad you’ve already tried some of the recipes and are noticing improvements. Small, consistent steps can really add up over time.

Constipation is very common with hypothyroidism and can also be influenced by gut health, hydration, fiber, magnesium status, and medications or supplements. I also have an article on constipation and thyroid health (link below) that you may find helpful if you haven’t seen it yet, along with additional options to discuss with your healthcare provider.

Thank you so much for your kind words, and I’m really glad the information has been helpful on your healing journey. 😊

Here is a link to the article:

SOLUTIONS FOR CONSTIPATION RELIEF

https://thyroidpharmacist.com/articles/solutions-for-constipation-relief/